Recently declassified documents published to the Russian FSB website are claimed to contain information provided by the so-called ‘Cambridge Five‘ – the notorious spy ring that provided information to the Soviet Union from the 1930s to the early 1950s. The documents deal with Poland’s efforts to prepare for a post-war world in which that country might enjoy familiar borders and a more democratic style of government. With their British assets in place during high-level meetings, the Soviet Union always had the upper hand to ensure Poland would rest fitfully under the oppressive thumb of Communism.

The set of four translated documents provided in this post originally come from pivotal points in what would be Poland’s future. We have to rely on the good word of the FSB that the information contained in each does, indeed, originate from the activities of Philby and company, as they are (rightly so) never identified in the text. Oddly enough, a number of portions will be noted as still requiring redaction, with this or that word, name, or phrase obscured from our prying eyes, some 80 years after the ink dried.

But why publish these documents now? We suspect that the publication of documents that, from a Soviet-eye-view, tries to show Poland as a land-grabbing back-stabbing false friend, and perhaps serves as Russia’s warning that Poland has ulterior motives in its vociferous support for Ukraine. Just a guess.

What follows is an edited introduction to the documents, as translated from the Russian website. We’ve removed most of the inflammatory language, because it distracts from the true history of the actual events.

Prelude

During the Second World War, the “Polish question” was a stumbling block between the leaders of the “Big Three” more than once. In Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam, the heads of Great Britain, the USSR and the US spent hours discussing the fate of Poland, finding compromises with difficulty. The legendary “Cambridge Five” played a significant role in the fact that the Soviet point of view ultimately prevailed, reporting valuable information to Moscow both about the plans of the Poles themselves, including the provocative policy of the Polish government in exile based in London, and about all of the changes in the positions of the Western allies.

In 1938, during the so-called Sudetenland Crisis, Hitler decided to put pressure on Czechoslovakia to cede the German-populated Sudetenland to Germany. Moscow declared its support for the Czechoslovaks, but the situation was complicated by the fact that the USSR did not have a common border with Czechoslovakia, and in the event of a conflict, much depended on Poland and Romania, who had to decide whether or not to grant right of passage through their territories to help Prague.

Thanks to the intensive work of the Cambridge Five, the Soviet intelligence network in London, Moscow knew in advance that the Poles would be forced to side with the Nazis before Soviet troops could come through. The London residency promptly sent copies of the reports of the British Ambassador in Warsaw, Howard Kennard, to the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the UK, Lord Halifax, to the Center. Thus, on May 18, 1938, Kennard informed his boss that “Poland could accelerate the onset of the crisis,” without ruling out an “open manifestation of hostility” by Warsaw toward Prague.

The reasons for this were that the Poles had been laying claim to the Cieszyn region, a small but strategically important region in Silesia with a mixed Czech-Polish population, since 1920. After signing the treaty with the Germans in 1934, the Polish secret services, represented by the 2nd Department of the General Staff of the Polish Army, began to carry out destabilization activities there, including training terrorist groups, in order to obtain a pretext for seizing the region.

Moscow knew in advance that Warsaw would take their chances with Hitler, and was aware of the risks associated with a joint action by Poland and Romania against Soviet “assistance” to Prague. According to a report by G. Kennard on June 3, 1938, a copy of which was in the possession of the Soviet authorities, the Chief of the General Staff of the Romanian Armed Forces visited Warsaw the day before, discussing with his Polish colleagues “coordination of measures in the event of the USSR entering military action.” The Kremlin was also informed about Warsaw and Bucharest’s detailed development of mechanisms for cooperation in a “campaign directed against the Soviets.”

Moscow was informed by the Cambridge Five that Paris would not show total support for Czechoslovakia. The tragic events of the autumn of 1938, known as the Munich Agreement, confirmed the veracity of the information provided by the Five: England and France, in essence, betrayed the Czechoslovaks, forcing them to submit to the dictate of the Third Reich. Poland, having treacherously seized the Cieszyn region, not only refused to let the Red Army pass to help Prague, but also threatened to shoot down Soviet aircraft, beginning large-scale maneuvers on the Soviet-Polish border.

The Polish policy predetermined the failure of the Anglo-French-Soviet negotiations that took place in Moscow in the summer of 1939. According to current Russian accounts, “Having finally become convinced of the dishonesty of the Western powers and the open hostility of Warsaw, Moscow was forced to conclude a Non-Aggression Pact with Berlin, thanks to which it was possible to win almost two years of peace to prepare to repel the aggression of the Third Reich.” Poland collapsed in September 1939 – a few weeks after Hitler’s attack.

War

The Polish leaders fled to Paris, then to London, where they formed a government in exile. This body was a source of squabbles and scandals throughout the war, seemingly complicating the already difficult relations within the anti-Hitler coalition.

At first, Moscow seemed to express readiness to cooperate with the London Poles. The Soviet Ambassador to Great Britain, Ivan Maisky, and the head of the Polish government in exile, Władysław Sikorski, signed an agreement to resume diplomatic relations in July 1941 in the presence of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. But this turned out to be in vain. Hoping to avoid what they felt would be Soviet troops setting foot on Polish soil for good, the London Poles were said to be frequently working against Moscow, trying to set the British (and Winston Churchill personally) in their favor. Their activity increased most markedly in 1943 after the defeat of the Germans at Stalingrad, when it became clear that the strategic initiative had passed to the USSR.

23 February 1943 – Enciphered Telegram from London

In February 1943, the Cambridge Five reported on the growing fears of the London Poles in connection with the confident advance of the Red Army. According to intelligence reports, the government in exile did not want the USSR to liberate the Polish lands, hoping to organize an uprising and seize power there before the Red Army arrived. Moscow, therefore, understood in advance that as soon as Soviet troops approached Poland, the Poles in London would try to start their own initiative. It was this adventurous plan that was carried out in the summer of 1944, when, against the backdrop of the advance of Soviet units, a poorly prepared Warsaw Uprising began on the orders of the government in exile, ending in failure and the needless deaths of thousands of Polish patriots. The Soviet authorities, thanks to the Cambridge Five, knew in advance about the intentions of the London Poles, as well as the fact that they “appealed to the British with a request to deliver weapons to Poland by plane, but were refused.”

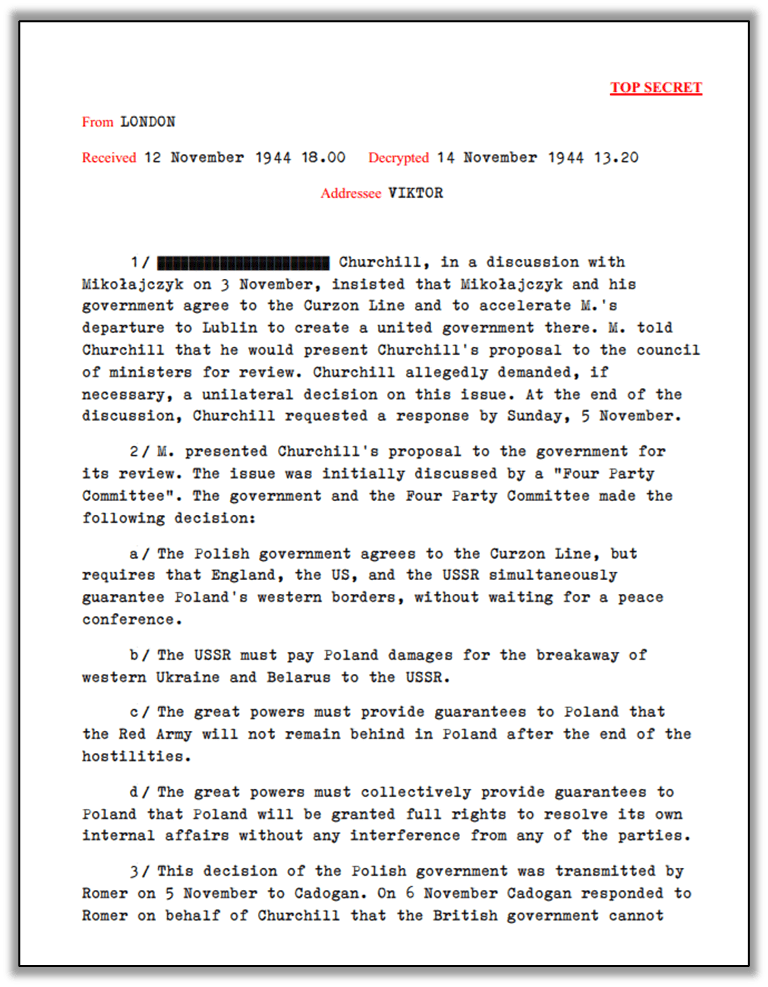

12 November 1944 – Enciphered Telegram from London

The information obtained by the Five was also useful to Stalin during negotiations in Tehran in November 1943, where the “Polish question” became one of the key issues. As a result, it was decided that after the war the Curzon Line would become the eastern border of Poland, i.e. de facto the West agreed to recognize the borders of the USSR formed after the annexation of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus to the Soviet Union in 1939. As compensation, the leaders of the “Big Three” decided to transfer part of Eastern Germany along the Oder-Neisse line to the Poles. Churchill even noted in this regard that the industrially developed German lands were “much more valuable than the Pinsk swamps.”

However, Stalin and his counterparts were already well aware that such a decision would be difficult to accept by the Polish émigrés, who continued to dream of Poland from “sea to sea”. Considering the position of the émigré government, the Allies decided to hide the agreements on the “Polish question” from the public for a while. Incidentally, Roosevelt insisted on this, fearing that the Poles would raise a fuss, and on the eve of the 1944 presidential elections, he did not want to lose the votes of the multi-million Polish diaspora.

In July of 1943, General Sikorski died in a plane crash in British Gibraltar. His place at the head of the government in exile was taken by Stanislaw Mikołajczyk, who in January 1944 declared a categorical non-recognition of the decisions of the Tehran Conference on Polish borders. The USSR, after the success of the Lvov-Sandomierz offensive operation and the entry of the Red Army into Polish territory, initiated the creation of the Polish Committee of National Liberation (PCNL) from among those Poles loyal to Moscow. It was this body that the Kremlin began to view as the representative for the will of the entire Polish people.

Nevertheless, Stalin was also prepared to talk with Mikołajczyk, who had visited the USSR on numerous occasions. In May-June 1944, on Moscow’s initiative, several rounds of confidential Soviet-Polish negotiations were held in London, where the Poles were offered various formats of cooperation. However, everything came up against the London émigrés’ demand for the restoration of the pre-war Polish borders, which was viewed as a non-starter.

Under these conditions, the Soviet leadership was increasingly inclined to cooperate exclusively with the PCNL. This was largely facilitated by the information coming from the Five about the attitude of the Western Allies themselves, who were also beginning to tire of the Poles’ attitude, toward Mikołajczyk and his “ministers.” Thus, in November 1944, intelligence reported to Moscow about the growing tension between the British and the Polish émigrés: Churchill, irritated by Polish willfulness, put pressure on Mikołajczyk, forcing him to accept the Curzon Line and pushing him toward dialogue with the PCNL.

However, the Poles, despite British appeals for common sense, could not come to a common opinion on the issue of recognizing the eastern borders. And even those who were generally ready to agree to the new borders set conditions that were completely divorced from reality. For example, they demanded that Moscow pay compensation for Belarusian and Ukrainian lands, as well as guarantees that after the war the Red Army “would not linger in Poland.” Churchill, as intelligence reported, directly told Mikołajczyk that London “would not give them any guarantees,” and proposed going to the USSR to resolve the border issue. Roosevelt acted in a similar manner with regard to the inflated Polish requests, about which the “Five” also promptly informed Moscow.

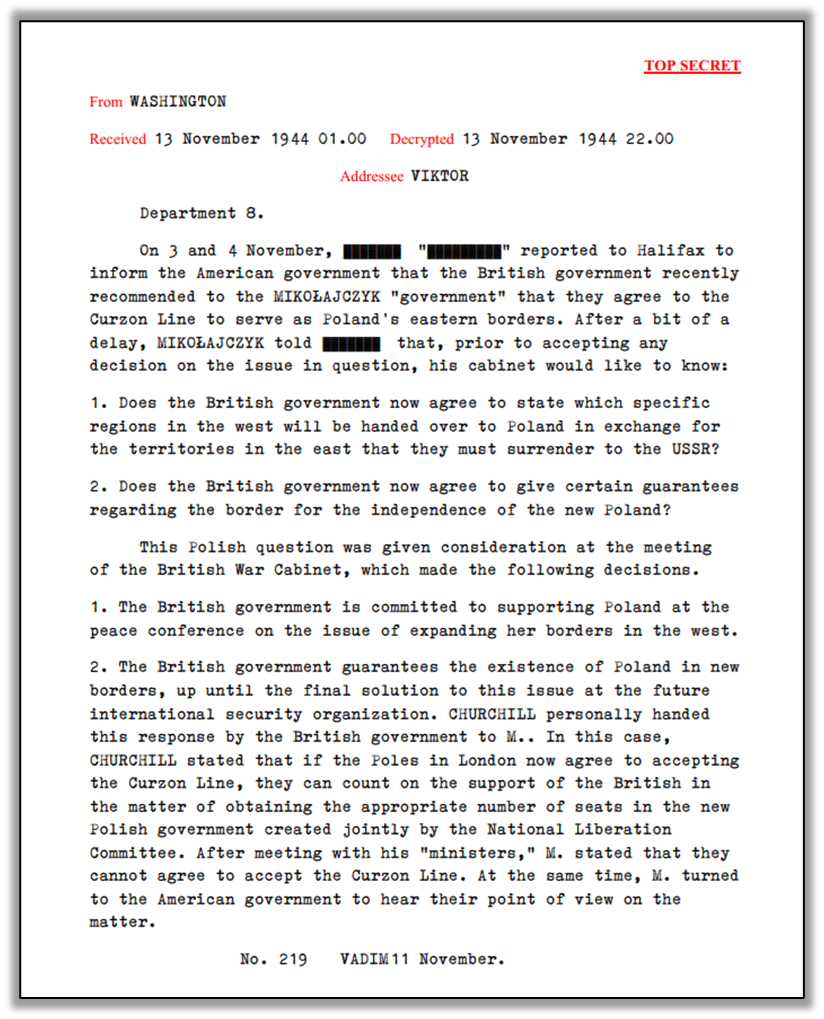

13 November 1944 Enciphered Telegram from Washington

Thanks to the continuing influx of intelligence, the Kremlin knew that Washington and London were advising Mikołajczyk and his associates not to harbor great-power illusions, but to concentrate on the distribution of seats in the future Polish government. The USSR leadership had a clear understanding that all the Poles’ claims were nothing more than unrealistic hopes, and they did not enjoy serious support from their Western allies.

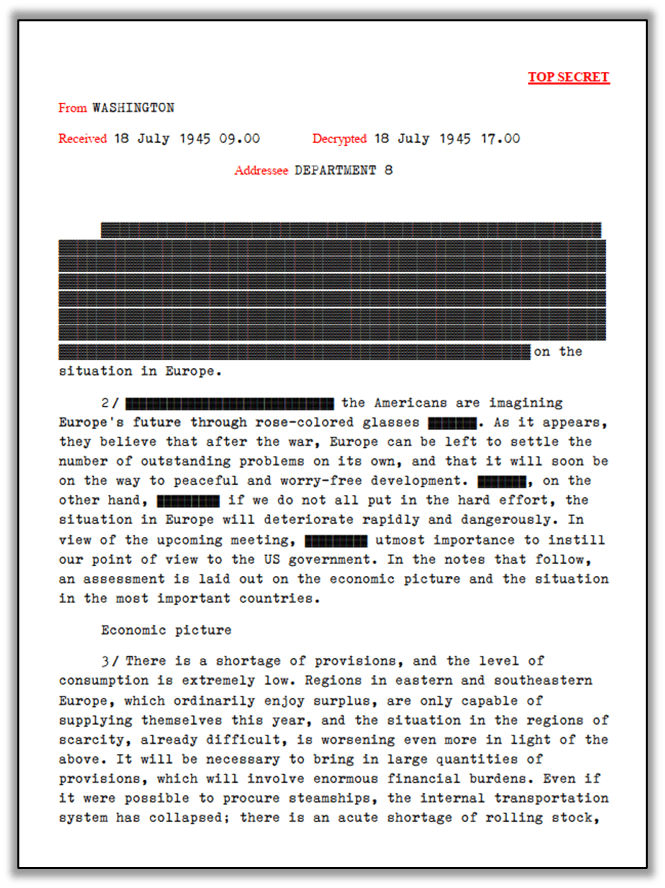

18 July 1945 Enciphered Telegram from Washington

All this valuable information was certainly taken into account when forming the Soviet position at the Yalta Conference in January 1945. On the eve of the new meeting of the “Big Three,” significant changes occurred in Polish affairs: in London, Mikolajczyk was replaced by the principled enemy of compromises with the USSR, Tomasz Arciszewski, in connection with which the PCNL declared itself the only Polish Provisional Government and was recognized as such by Moscow.

In Crimea, Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt came to an understanding on the general configuration of post-war Polish borders, agreeing that their final version would be agreed upon after Hitler’s defeat. The issue of the political structure of Poland was no less hotly debated. Thus, the British Prime Minister tried to defend the interests of London emigrants, although not out of sympathy for them, but in order to prevent the formation of a pro-Soviet leadership in Warsaw. It is significant that the head of the White House did not strongly identify with him, obviously realizing that it was the PCNL that represented the real force in Poland.

The debate in Crimea was indeed heated. Stalin insisted that, for the USSR, the “Polish question” was directly related to security, since over the centuries Poland had repeatedly been used as a springboard for aggression. “The Polish corridor cannot be closed mechanically from the outside by Russian forces alone. It can only be reliably closed from the inside by Poland’s own forces. For this, Poland must be strong. That is why the Soviet Union is interested in creating a powerful, free and independent Poland,” the Soviet leader emphasized.

As a result, in Yalta the “troika” declared their desire to create a “strong, free, independent, and democratic Poland.” In essence, Moscow managed to implement its plan: the Western allies did not interfere with the emergence in Warsaw of the Provisional Government of National Unity based on the PCNL, which de facto meant the bankruptcy of the political claims of the London Poles. And although Mikołajczyk was able to join the first post-war Polish cabinet (he took the post of Minister of Agriculture and Agrarian Reforms), neither he nor other anti-Soviet forces had much influence on Warsaw’s policies.