The following is a translation of a remarkable Russian-language article from Carnegie Politika, from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP). If you follow current global events but do not subscribe to CEIP’s news feeds or podcasts, do yourself a favor and make that happen today.

The article presented today is clearly a break from our standard fare, but given the importance of the chess match being played out by the West, Russia, and Ukraine, we are in the midst of seeing history being made in real-time, and any opportunity we can take to make excellent foreign-language journalism available to English speakers is worth the pause.

Today’s piece is authored by Alexander Baunov (Александр Баунов) – well worth following along with the rest of Carnegie’s team.

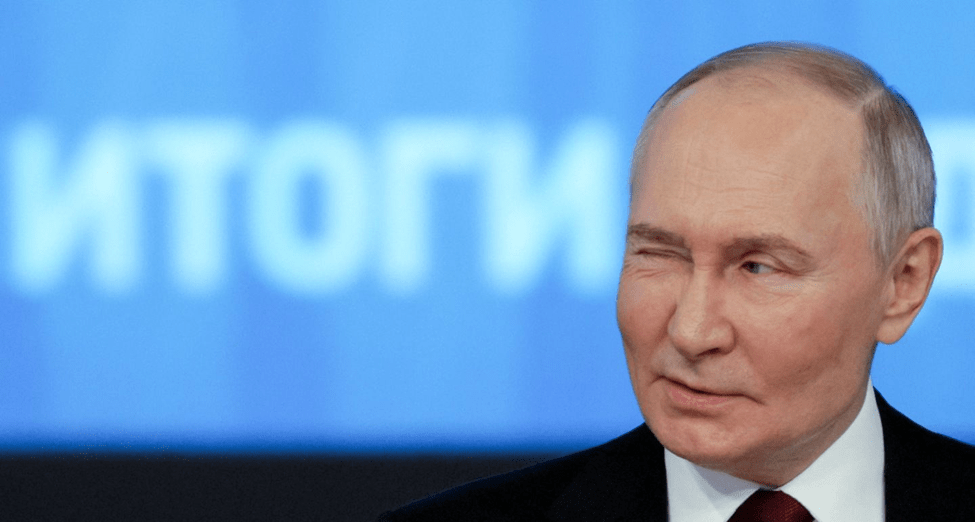

Force or Legitimization: Why Putin Needs Direct Talks

Alexander Baunov – 12 May 2025

While Donald Trump is torn between two statements: “Putin wants peace” and “Putin is just tapping me along,” Vladimir Putin has his own dichotomy. It is similar to the one described in a fundamental book on the Cold War [To Run the World] by Sergey Radchenko, a professor at Hopkins University. He recalls how Stalin, immediately following World War II, was torn between the desire to seize as much as possible and the desire to legitimize at least part of what was seized, even at the cost of some concessions.

At the time, it was yet another manifestation of the vacillation between force and legitimacy that is typical of Russian foreign policy. Moscow could afford to take a lot by force, but legitimacy came from Western capitals, above all Washington. And there they considered that Russia was demanding too much – for example, territories that it had not even conquered: part of Libya, the Turkish Straits, northern Iran, or the island of Hokkaido. And it was interpreting too broadly the liberation of part of Europe from the Nazis as a mandate to establish communist regimes in spite of election results.

We are now seeing in Putin’s behavior an attempt to grope for this narrow path between two ways of holding on to his conquests — by force alone or with the help of external legitimization. Under the previous White House administration, there was little hope of legitimizing what had been seized, but after Trump’s return, they have been revived.

The Russian leader would clearly be flattered by the comparison with Stalin. He has just renamed the Volgograd airport Stalingrad – “at the request of veterans of the SVO [special military operation]” – and a bust of Stalin was erected in captured Melitopol. The very context in which Putin proposed to begin direct negotiations is intended to support this parallel.

Putin made the proposal the night after the parade, either as the heir to the victors, or as the almost-victor himself. He spoke immediately after the decorated column of SVO participants marched through Red Square, putting the veterans of World War II on an equal footing with the conquerors of Ukraine. He spoke immediately after a long series of meetings with foreign leaders, who greeted the newly-minted veterans from the stands: why not the head of a new “anti-fascist coalition”? Even the night-time press conference imitates Stalin’s “window in the Kremlin whose light is never extinguished” – just now, in the anniversary film for the 25th anniversary of Putin’s rule, Russian television viewers were shown his Kremlin apartment and its owner – who also works at night.

Between a fixed match and a victory

Putin tried to frame his statement overnight in such a way that it would not be seen as an agreement to the Ukrainian proposal for an immediate 30-day ceasefire, which was strongly supported by the European leaders who had come to Kyiv. In Moscow, it was called an ultimatum, and Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov pointed ouit that Russia does nothing under pressure.

Everything has been done to ensure that Moscow’s proposal does not look like the result of pressure from Washington. While President Trump also approved a 30-day ceasefire, Putin came up with a completely different idea. He came from the opposite end: he proposed starting negotiations without a ceasefire. Or, more precisely, resuming the negotiations that were interrupted in Istanbul in the spring of 2022, which also took place in parallel with the fighting.

This is reminiscent of Moscow’s previous concession: the agreement to a de-escalation in the Black Sea in late March. It was also important for the Russian leadership to emphasize that nothing new was happening: the grain deal, which was not extended in 2023, was simply being resumed. Moscow is presenting its new initiative in a similar way: nothing new is happening: after a long break, we are simply proposing to resume the 2022 negotiations, interrupted by Ukraine at the behest of the West. That is, we are not proposing negotiations because Trump wanted them.

Even the first leaks that Putin would propose negotiations after the Victory Parade appeared with reference to sources in China, in particular to the words of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. In his nightly speech, Putin presented the initiative as a product of joint efforts: among those he thanked “for their mediation efforts” were China, Brazil, other countries of the Global South, but also – “recently” – the new US administration.

Even the proposed date for the start of negotiations – May 15, not May 12 – was chosen to show that the Russian initiative was not a response to the Ukrainian proposal or the result of someone’s pressure, but something completely separate and independent.

Putin’s initiative also better serves Russia’s interests “on the ground.” Russian spokesmen have repeated time and again that a simple ceasefire gives Ukraine a military advantage, which will use the pause to build fortifications, safely produce and import weapons, and conduct mobilization. Putin’s proposed negotiations without a ceasefire, on the contrary, give Russia an advantage. The Russian army will continue to advance on the front and bomb behind Ukrainian lines, backing up diplomatic pressure with military pressure.

The chosen format of the counter-proposal allows both to prevent or postpone Trump’s angry exit from the negotiations, which he announced in the event of non-cooperation from one or both of the parties. And at the same time, to calm his own entourage, the military, external observers and, finally, the pro-war part of Russian public opinion, which fears most of all a “deal” and a “new Minsk”.

The stability of Putin’s power seems essentially independent of public sentiment, but both to achieve peace and to possibly continue the fighting, the Russian leader needs social support – and especially its ultra-patriotic segment.

The emphasis on Russia only resuming the interrupted Istanbul talks is best suited to balancing between compromise and the desire to fight, between legitimacy and force. After all, what were the 2022 talks about if not Ukrainian concessions in exchange for an end to Russian aggression – that is, the conditions for a Russian victory? Back then, neither Ukraine nor the West were ready to legitimize Russia’s conquests; now they are more ready. Trump is directly pushing Ukraine to make concessions.

However, even the current American administration, judging by Trump’s threats to either slam the door or move on to some new, especially crushing sanctions, turned out to be unprepared for the volume of Russian demands. Trump responded to the Russian initiative ambiguously: on the one hand, he urges Zelensky in all caps to immediately agree to direct negotiations and go to Istanbul, on the other, he does not express confidence in their success, but only notes: at least there will be clarity and “European leaders and the United States will know where we are.”

Zelensky repelled the Russian attack that same day, announcing that he would be in Istanbul on May 15 for a personal meeting with Putin. Thus, anticipating events (usually top officials meet when delegations have already reached an agreement), he is trying to show that the Russian proposal is aimed not so much at achieving peace faster, but at prolonging the war.

A generous offer – or a bare-bones agenda

When Trump promised a quick peace, he seemed to have fallen victim to yet another rationalization of the motives that led Putin to war. This rationalization is widespread in Western public opinion far beyond the current White House. To some extent, it is a product of Russian propaganda, which, in justifying aggression to an external audience, chose the most rational argument – supplying, like the Soviet automobile industry once did, a higher-quality product for export than for its own market.

This argument is called “the war caused by NATO expansion.” And although even a cursory glance shows that NATO expanded in many directions, and its chances of expanding into Ukraine were vanishingly small, the causal link between the Alliance’s expansion and the war appears most convincing to Western public opinion.

Hence Trump’s simplified understanding of the path to peace. Biden confirmed the possibility of Ukraine joining NATO, which provoked a Russian attack – so NATO’s doors need to be officially closed for Ukraine, and the causes of the war will be eliminated.

However, in 100 days in power, the Trump administration has realized that to stop aggression, Russia requires eliminating a much broader set of “root causes of the conflict.” Instead of one point about NATO, it is necessary to meet Moscow halfway on many points, agreeing to revise some of the results of the West’s victory in the Cold War. Or not.

Trump has already expressed his readiness to officially recognize Crimea as Russian and to effectively control Russian territories along the front line, to begin the process of lifting sanctions, to normalize trade and diplomatic relations, and to allow Moscow to participate again in resolving global problems. This is the legitimization that could encourage the Kremlin to renounce the further use of force.

In Trump’s mind, he is making a generous offer. However, Putin’s repetition of the formula about “eliminating the root causes” and their expanded interpretation by his subordinates suggests that Moscow has not yet abandoned its maximalist demands. That if Putin is not against peace, then it is peace on terms close to those set out in the ultimatums to the West in the fall of 2021 and the “goals of the special operation” declared in the spring of 2022. What Washington is ready to accept as a maximalist demand position for the start of peace negotiations, Moscow still considers something like a bare-bones agenda.

Trump is willing to go very far with Ukraine, explaining that concessions can be made to persuade Putin not to conquer the entire country. However, even Trump, who is not very well disposed towards Zelensky and the Europeans, does not understand how to cede territories “that Russia has not even conquered,” lift foreign sanctions, or force Europe to succumb to Russian pressure. Coupled with Moscow’s claims to be able to influence not only the presence of foreign bases and the makeup of the armed forces inside Ukraine, but also language and education laws, issues of historical memory, and even elections, this makes even the current American administration say that Moscow “wants too much.”

However, Russia is increasingly living by war. The image of the enemy is becoming more and more demonic, combatants are increasingly heroized and equated with veterans of the Great Patriotic War, there are more killed and wounded in villages and cities, the military economy has more and more beneficiaries, and more and more “traitors” are being repressed. Even in the nighttime proposal for negotiations, Putin used the word “war” and not SVO.

The longer and more extensive the military effort, the more convincing its result must be. Three years of talk about a war against “rising Nazism” have narrowed the field for ideological maneuver: after all, you don’t negotiate with Nazis – you defeat them. For this reason, what Trump considers a generous offer will not be easy to formalize as a victory inside Russia.

The absence of many sanctions, SWIFT [Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication] and air traffic, global brands, and control over Crimea already existed before the current war. And the legal subtleties of recognizing this control are of much less concern to most Russians than to diplomats. Even the Ukrainian leadership, before the start of the large-scale war, said that it was not considering the option of a military return of Crimea, postponing it to a distant hypothetical future. With such an image of victory, similar to the pre-war reality, the question arises: why did they fight?

After three years of war, in addition to Crimea, Russia controls the same two regional centers as before, adding to them several district centers of varying importance and 100 thousand square kilometers – the size of Portugal or Bulgaria – although mostly scorched earth. Moreover, the international legal status of these two regional centers and Crimea has not changed even for the countries of the “global majority”: they are essentially not considered Russian territory anywhere.

Symbolic goals important to militant patriots, such as Kharkiv and Odesa, a change of power in Kyiv and a revision of Ukrainian laws, have also not been achieved. Such an image of victory is difficult to sell not only to the Russian population, but also to include in the series of glorious victories of great rulers of Russia, which undoubtedly worries Putin, who is immersed in the continuous study of historical literature, lecturing on history to journalists and foreign leaders.

This is precisely the reason for the Kremlin’s paradoxical insistence on recognizing unconquered territories. Actually holding on to what has actually been captured is a local success of arms, a limited victory of force. But to force the ceding of unconquered territories is a dismantling of the opponent’s political will, a tangible success not only in terms of force, but also in legitimizing the most diverse, even absurd, Russian demands.

A new old Yalta

While the Kremlin has emphasized its inflexibility, in various ways speaking of “addressing root causes,” it has had to abandon some of the maximalist positions it hastily adopted during the sharp cooling of relations between Zelensky and Trump. At that time, it seemed possible to test demands such as a complete end to military aid, UN external governance in Ukraine, or Ukrainian elections as a precondition for negotiations.

The White House rejected these ideas, so there is no longer any talk of the complete illegitimacy of Zelensky and the entire Ukrainian system of power, which, as Putin said at the end of March, is in the hands of neo-Nazi groups. Moscow no longer insists, as it did in the first months of the year, on talking about peace in Ukraine only directly with Washington without Ukraine’s participation. The demand to cancel the law banning negotiations with Putin by vote in the Rada before the negotiations has been removed. The proposal to begin direct negotiations arose in the context of a kind of peace competition between Kiev and Moscow in the face of the new American administration.

Other signs of flexibility in the Russian position – such as a Financial Times article that cited six sources as saying Putin was prepared to agree to a frontline resolution without handing over to Russia anything unconquered – were disavowed by Peskov, Lavrov, and other officials.

The Trump administration assumes that after three years, Russia is tired of war, so the prospect of restoring relations in exchange for an end to hostilities and territorial gains is enough for the Kremlin to agree to peace. Moscow, on the contrary, believes that the other side has a combination that is advantageous to it: Ukraine’s exhaustion, the West’s fatigue, Trump’s lack of interest in Ukraine, and hostility toward Zelensky will lead to the implementation of the remaining points of the Russian ultimatum by peaceful means. The threats of new crushing sanctions that Trump periodically voices publicly and conveys through Russian negotiators are softened by his inconsistency in the tariff war with China and others.

Earlier, and even more so than in the Trump administration, the image of a grand bargain between great powers was popular in Moscow. Here, the example of such a deal is Yalta, which supposedly sealed the Western allies’ agreement to a Russian sphere of influence. Hence the constant desire for a “new Yalta” — that is, diplomatic legitimization of Russia’s current claims.

Few remember that Yalta actually failed. The percentages of influence in different countries in southeastern Europe that Churchill and Stalin had written down on a napkin were not observed; no Yalta was supposed to transform the states of Central and Eastern Europe into communist dictatorships; they were only able to be imposed by force. A cold war, a civil war in Greece, a Berlin crisis, and, finally, the Korean War, which began with Moscow’s approval, unfolded – the first proxy war in history between countries possessing nuclear weapons, in which many then saw the kickoff of World War III.

Frozen in a delicate balance between force and legitimacy, even retreating from some of his demands in Asia and Africa, Stalin ultimately chose force as a more reliable way to hold on to what he had won. Putin is in similar contemplation, and it is possible that, having gone through similar doubts, he, not trusting the West as a source of legitimacy, will make the same choice.