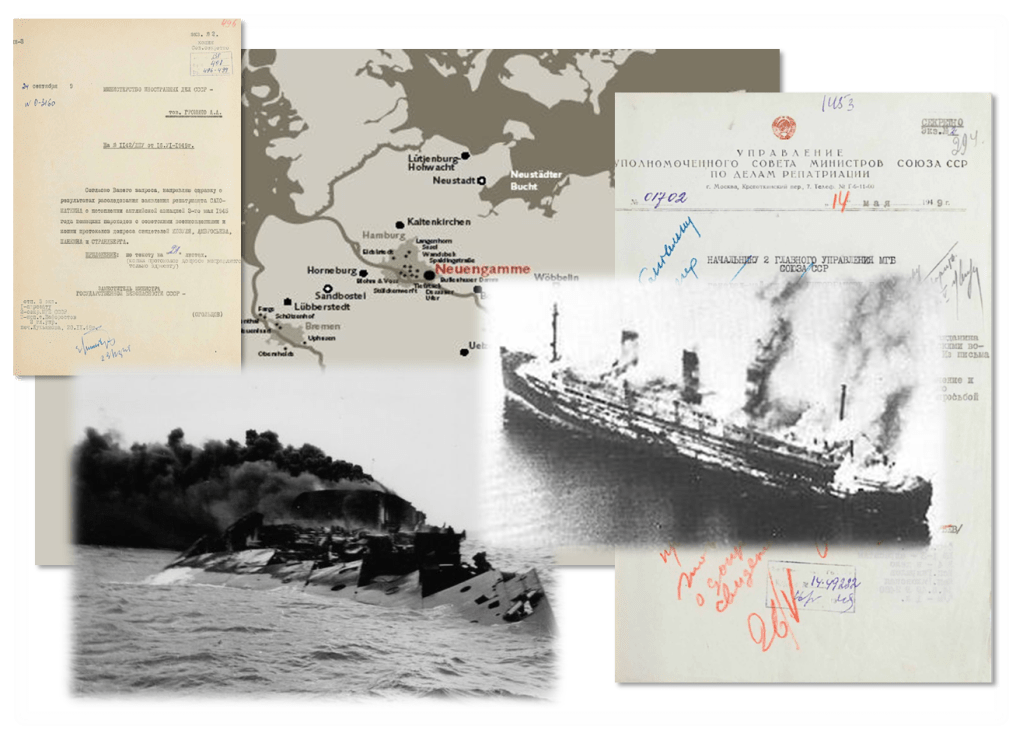

Earlier this month, the Russian FSB declassified and published a set of documents that offer eyewitness survivor testimony to the Lübeck Bay tragedy, and event that claimed the lives of thousands of prisoners of war.

On 3 May 1945, with only a few days left before Germany’s final capitulation, the Royal Air Force conducted bombing raids on three German transports. According to various estimates, there were between 7,000 and 12,000 prisoners from German concentration camps on these ships, many of them Soviet prisoners of war. Tragically, only about 300 people survived.

At the end of the war, Himmler issued a secret order to evacuate the concentration camps. Thus, on April 19, 1945, a hasty evacuation operation began in the Neuengamme concentration camp in order to cover up the traces of the crimes of the Nazi regime. In the last days of April 1945, the SS sent more than 10,000 prisoners from Neuengamme to Lübeck on foot or in freight trains.

On May 2, 1945, the SS delivered several thousand concentration camp prisoners from Stutthof near Danzig, Neuengamme near Hamburg, and Mittelbau-Dora near Nordhausen on barges to the liner Cap Arcona, the cargo ship Thielbek, and the ships Athen and Deutschland, which were moored in the harbor of Lübeck. The German command reportedly informed representatives of the Swedish and Swiss Red Cross missions about the upcoming convoy. On May 2, the mission staff passed this information on to British General George Roberts, whose troops were advancing in the Lübeck area. For some unknown reason, Roberts did not forward the information he had received to the British Air Force leadership. As a result, the British pilots methodically bombed and sank the ships.

Later, what happened was called “one of the greatest tragedies at sea in World War II” in world historiography. However, no official investigation followed. The scale of this massacre became known only several years later, thanks to the testimony of surviving prisoners of the Neuengamme concentration camp who returned to the USSR.

The FSB published a number of declassified documents from the Central Archive of the FSB regarding these events. Primary among them is a letter from Vasily Salomatkin, sent on May 2, 1949 to Colonel Vasily Vaneyev in the Office of the Commissioner under the Council of Ministers of the USSR for Repatriation of Citizens of the USSR. Salomatkin reported in detail on the destruction of ships with prisoners of Nazi concentration camps in Lübeck Bay by British warplanes and boats.

It is worth noting that the FSB does not declassify and publish documents thoughtlessly. They have used the Internet and hardcopy publications to forward an agenda no doubt encouraged by the Kremlin, and almost always with a view to embarrassing today’s Western powers. The FSB-written material that accompanied this package of documents uses heavy-handed emotional words to more than suggest that the British were not only fully aware that the ships were carrying POWs, but that they took glee in recognizing them as such while continuing to strafe them in the water and on the boat decks. Many historians have argued, however, that unlike other ships used to transport POWs to neutral countries, the three in question on 3 May 1945 were not painted with a red cross on a white background to identify it as a ship being used for humanitarian purposes. Strong arguments are also made that Himmler and his associates felt that, because of the missing paint scheme, there was a good chance of having the Allies eliminate the POWs, thereby saving the Nazis the need to do away with thousands of witnesses to the atrocities of the concentration camps themselves. Also noteworthy is the clear effort to make use of the tragedy as propaganda against the British.

Just something to keep in mind while reading the translated material.

Regardless of the unknowns, the event was clearly a tragedy of the highest order.

What follows is our translation of the package regarding the original letter from Salomatkin, the subsequent investigation, and follow-on testimony from other witnesses who survived the attack that day.

Copy No. 2

Top Secret

24 September

USSR MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS

Comrade A. A. GROMYKO

To No. 1142 DPU / dated 16 June 1949

In accordance with your request, I am forwarding to you the official document on the results of the investigation of the statement by repatriate SALOMATKIN on the 3 May 1945 sinking by British aircraft of German steamships carrying Soviet prisoners of war, and copies of the records of questioning of witnesses KOZUL, AMVROSYEV, PANKIN, and STRANDBERG.

Attachment: per text, 21 pages.

(copies of interrogation records are being sent only to addressee)

DEPUTY MINISTER OF

STATE SECURITY OF THE USSR (OGOLTSOV)

OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER UNDER THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS OF THE USSR FOR REPATRIATION OF CITIZENS OF THE USSR

Colonel VANEYEV

ATTACHMENT

to the Complaint of V.F. SALOMATKIN

Esteemed comrade Colonel! You have asked me to provide a detailed description of the sinking of the ships carrying 12,000 prisoners of war by British aircraft on 3 May 1945, 6 km from Neuenstadt (Holstein).

Comrade Colonel! Your message to me with this request both alarmed and delighted me, for this is the first time I have encountered a man specifically interested in the facts and details of the sinking of the prisoner of war ships by the British aircraft. I no longer expected anything of the sort, as I’ve talked about it several times and nobody seemed interested in the events, and never paid it any mind. Meeting someone interested in this event, I’m delighted to report the specific details of the sinking of the ships with prisoners of war by the British aircraft.

On 29 April 1945, the SS command, sensing the approach of Allied troops toward the Neuengamme concentration camp (near Hamburg), removed all of the concentration camp prisoners who could still barely move to Lübeck. We numbered 12,000. The overwhelming majority were Russian prisoners of war. We were brought to Lübeck day and night by train. We were given nothing at all to eat or drink. We were transported under increased SS security. In Lübeck we were placed on barges, and under heavy guard by soldiers and boats, we were transported via Lübeck Bay to the Baltic Sea, where there were one large and two small ocean-going ships. About two thousand prisoners were placed on each of the two small ships. One of the small ships was called the Thielbeck, and the second one I can’t recall. Some 8000 prisoners, including me, were put on the large ship. This ship was called the Cap Arcona. The commands aboard the ships were SS. I don’t remember the names of the ship captains.

On 3 May 1945, English troops had approached Neuenstadt, and demanded the city’s surrender by noon. The city acceded to the capitulation. Following this, the ships on which we were located were instructed to capitulate as well, by 3 in the afternoon. The ships were six kilometers from Neuenstadt. The SS commands aboard the ships refused to capitulate. Afterwards, large numbers of aircraft flew in and began bombing the ships that we were on.

The ships we were on returned no fire on the English aircraft. I personally observed the entire panorama of the bombing of the English aircraft. During the bombing, there was total disorder among the SS men on our ship. I and a small group of prisoners took advantage of this, and during the confusion we managed to get out on deck, where we observed the entire panorama of the bombing.

The first victim of the bombing was the ship Thielbeck. She immediately caught fire and began to sink. The prisoners who were able to break out from within the hold jumped into the water. After the first English bomb struck the Thielbeck, the SS command of the ship Cap Arcona, where I was located, raised a white flag, signifying surrender. The prisoners who were on the deck took off their undershirts (they were white) and began waving them, signalling to the English pilots that the ship was surrendering, accepting capitulation, but the English pilots, just like the Nazi pilots, not recognizing anything, not paying attention to the white flag on the ship, not paying attention to the waving of white shirts by the people on the deck, asking for mercy, for their lives, continued to bomb the ships. The bombing took place at a very low altitude. The English pilots saw all the horrors of their bombing and continued to do it even more, paying no heed to any of the pleas from the people. The English pilots in their brutal reprisals are no different from the barbarian Nazi pilots.

The second victim after the Thielbeck was the second small ship. Then a bomb hit the stern of the Cap Arcona, and at the time I was on the bow of the ship. The SS dropped boats into the water when this happened, and fled. On the Cap Arcona, panic broke out among the prisoners. The prisoners streamed up to the deck. At that time, a second bomb hit the middle of the ship, and the ship caught fire and began to sink. As a result of the panic, the prisoners tried to get up to the deck, pulling each other from the ladder, and so nobody could reach the deck, instead being left inside the ship, so they sank with it. After the second bomb hit the Cap Arcona, I, along with other Russian prisoners, jumped off the ship into the water. About a kilometer from the place where the Cap Arcona sank, torpedo boats appeared. Seeing them, we rushed to meet them, thinking that they would pick us up and save us. It turned out to be the opposite. The soldiers on the boats stood and shot the swimming prisoners with machine guns. I was saved from the fate of being killed by a soldier’s bullet from his machine gun because I was unable to swim any closer to the boat, unlike so many others, and I was some 400 meters away from the boat. Seeing what was happening, I turned back and headed to shore. The shore was barely visible; I swam unassisted by any other means than my own arms and legs. I, too, would not have made it to the shore, like the others, but my misfortune was met with good fortune; I had already swum a good distance and the sea tide began to come in, thus saving my life. By this time I was completely exhausted and the waves brought me ashore. I was only semiconscious by then. Through my hazy eyes I saw white buildings and the movement of people on shore, but I was unable to make out men from women. And when my chest struck the beach, I completely lost consciousness. Shortly after, the Russian concentration camp prisoners, who were stronger than me and had already reached shore, pulled me from the water’s edge and began performing artificial respiration, and when I had somewhat come to my senses, I was shipped off to the hospital. And the British were there at the time.

In the English hospital set up for the survivors, I regained consciousness on the second day, after which I learned that out of 12,000 prisoners, only 300 were saved, the rest were victims of the bombing by the Royal Air Force that took place on 3 May 1945 at 3 in the afternoon.

Among the Russian POWs rescued were:

1. BUKREYEV Vasily Aleksandrovich – Ryazan Oblast, Muravlyanka region, village of Toptykovo

2. GORDEYEV Ivan Ivanovich – Ryazan Oblast, Skopin, 17 Ulitsa Novikova

3. MOROZOV Vasily Zakharovich – Chkalov, 133 Ulitsa 12 Dekabrya

4. SHTUTSOV Vasily Mikhaylovich – Kherson, 41 Ulitsa Dzershinskogo

5. AMVROSYEV Sergey Grigoryevich – Tula, Pirogova, 19

6. CHERIKOV Georgiy Ivanovich – Tula, 2 Ozernaya, 3

7. TSIBROVSKIY Edmund Ivanovich – Kyiv, settlement Vorzel, 17 Ulitsa Lenina

and many others whose surnames I recall, but whose addresses I don’t.

Comrade Colonel, if you question these individuals, and write about me, call me ANTONOV Vas[ily] Fil[ipovich], as I was in the concentration camp under the name ANTONOV, and these individuals will only know me by this name.

After I left the hospital, I was in a camp for the survivors. The English treated us rather improperly. They herded us into cramped quarters, and fed us poorly – only German canned rutabaga and spinach. At one point, when we protested and wouldn’t take this food, and demanded actual food, they responded, “You are not even worth this.” After which two of the former POWs were arrested, charged with sabotage, and imprisoned. I have no idea what their fate was. I left camp, and they remained in prison. We then wrote to file a complaint to General-Colonel GOLIKOV, complaining about the poor food. After some time, the city commandant was replaced and while the food improved, it still did not meet the requirements that were set forth at the Yalta Conference, that our prisoners of war would be able to use the same rations as that of the British soldiers. A little while later, bodies started washing ashore, the bodies of the prisoners of war from the ships that were sunk by the British aircraft on 3 May 1945. They had to be buried. A mass grave would have to be made, honors arranged. We Russians selected a committee for burying our dead comrades, the victims of the British bombing. The committee, which I was a member of, approached the English captain, the commandant of the city of Neuenstadt for help (I can’t remember the name of the commandant) so that the British commandant’s office could offer assistance and take part in the burial of these comrades. The city commandant promised to allocate one ship for purposes of rendering honors and offering a salute. When the graves were ready, we once again approached the commandant to report that the burials would be tomorrow, and asked for his participation. The commandant responded that he would be unable to allocate a ship. We then told him that he, too, was a victim for these comrades. After this, he agreed to the burials and would select an artillery battalion for the salute. The next day, we led the funeral procession through the city. When we approached the commandant’s office to inquire as to where the artillery battalion was for the salute, the commandant replied, “I’m not giving you anything, go bury them as you wish, I have nothing for you.” That’s how the British treated their Russian Allies. And we did as best we could, rendering honors to our comrades, the victims of the Royal Air Force. This is how the British treated us.

The second event occurred when we were in the camp, rescued from the ships. At that time, the British herded German prisoners of war into the entire city. They walked about freely, sauntering about, attacking and beating our surviving prisoners of war, threatening to cut us all to pieces at night, because they were walking around with bladed weapons. After these threats, we went to the English commandant and reported this. The commandant only smirked and took no effective measures. Not having received a satisfactory response, we came to the camp and there we announced to our people that they should get their hands on weapons for self-defense. Having done so, we established our own guard in the camp and protected the camp from attack by the Germans. These were the conditions we endured with the English.

After this, I was called to the military mission for the repatriation of Soviet citizens, where I encountered outrageous events that were hostile to the Soviet Union. The British would constantly speak among our prisoners of war, calling on them not to return to the Soviet Union, especially among the Ukrainians, Latvians, and Estonians.

So this, comrade Colonel, is a description of the facts of the sinking of the ships with 12,000 prisoners by British aircraft on 3 May 1945. Of course, this is far from a complete description, for I’m unable to immediately recall many of the details at present.

Comrade Colonel! I believe that, from these facts, you can imagine the difficult path I’ve trodden, what heavy hardships I’ve taken on, the persecution we all have been subjected to. And in spite of all this, I know people in my homeland who never heard gunfire, who pay no heed to any of my sufferings, and who ostracize me, and don’t offer me work. How am I to endure this?

Comrade Colonel, put yourself in my shoes, please help me, because I still am not working yet.

Comrade Colonel, I have high hopes for your assistance in helping me find work.

I’ve written everyone, but I have yet to receive a satisfactory reply from anyone, everyone responds, referring to different places, but I can’t get work here because I was in prison. You are my only hope, the Office for Repatriation of Citizens of the USSR. Unless I receive a satisfying answer from you, I only have one way out – to do away with my life. There is no other way out.

With regards, V. Salomatkin

Moldovan ASSR, Krasnoslobodsk, 23 Ulitsa Molotova 2.5.1949

SECRET

DIRECTORATE OF THE AUTHORIZED COUNCIL OF MINISTERS OF THE USSR FOR REPATRIATION AFFAIRS

No. 01702 14 May 1949

TO THE CHIEF OF THE 2nd MAIN DIRECTORATE OF THE MGB OF THE USSR

General-Major Ye. P. PITOVRANOV

Herewith I am sending you a copy of a letter from Soviet citizen comrade SALOMATKIN on the sinking of the three ships with Soviet prisoners of war by British aircraft on 3 May 1945. It is obvious from the letter than comrade SALOMATKIN is a witness.

Since this event carries fundamental importance and can be used against the British, I have sent comrade SALOMATKIN’s letter to comrade VYSHINSKIY with the request that a thorough investigation be established.

ATTACHMENT: on four pages, to the addressee only

DEPUTY OF THE AUTHORIZED COUNCIL OF MINISTERS OF THE USSR FOR REPATRIATION AFFAIRS

GENERAL-LIEUTENANT GOLUBEV

Top Secret

MEMORANDUM

on the results of the investigation of SALOMATKIN’s statement on the 3 May 1945 sinking of German steamships carrying Soviet prisoners of war by British aircraft

The USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs submitted a request regarding the statement of repatriate V. F. SALOMATKIN, who was a witness to the 3 May 1945 sinking of three German steamships with 12 thousand Soviet prisoners of war by British aircraft.

Questioned as a witness, SALOMATKIN confirmed the facts laid out in his statement, and reported that before the end of the war with Germany, he – along with other Soviet prisoners of war – were held in the German Neuengamme concentration camp near the city of Hamburg.

Because of the approach of the British troops toward Neuengamme, the Germans, gathering up some 12 thousand prisoners of war, loaded them into freight cars and, under tight security, sent them to the city of Lübeck, where they were loaded onto barges.

On 3 May 1945, escorted by German small combatants and submarines, the barges – carrying the prisoners of war – were led by tugs from Lübeck Bay to the Baltic Sea and led to three German steamships – the Cap Arcona, the Athen, and the Thielbeck, standing approximately 6 kilometers from the city of Neuenstadt.

All of the POWs were located on the steamships in question, with the largest of the three, the Cap Arcona, carrying some 8000 prisoners.

At 3 o’clock in the afternoon on 3 May, above the loading site, there appeared a group of 15-16 aircraft with British identification markings, which began bombing the steamships with the POWs on board.

In spite of the fact that the Germans raised the white flag, indicating their surrender, and the prisoners of war, having removed their white undershirts and waving the same in the air, the British pilots continued to bomb and strafe the steamships.

As a result of the bombing, the ships sank, and the prisoners of war held within perished, other than some 300 who were rescued.

SALOMATKIN’s testimony is confirmed by a number of interviewed witnesses from among those who survived the sinking of the steamships.

For example, witness V.D. KOZULYA, a former commander of a Soviet Army aviation detachment, who was questioned this past September 15, testified:

“On 27 April, along with other prisoners of war, I was placed on the steamship Athen, which carried us toward the steamship Cap Arcona, standing some 4-5 kilometers down Lübeck Bay, on which we were to be transferred.

“On May 3, 1945, at approximately one o’clock in the afternoon, I and other prisoners who were in a cabin of the Cap Arcona saw three Hawker Hurricane aircraft that were approaching our ship, and then dropped bombs on it.

“An hour and a half later, about thirty Hawker Hurricane aircraft appeared in the distance, eleven of which headed for the Cap Arcona. For 10-15 minutes, they fired intensively at it with machine guns and dropped bombs.

“A fire broke out on the ship and it began to sink. Having made it onto the deck, I jumped overboard.”

Witness S.G. AMBROSYEV testified:

“On 3 May 1945, at roughly three in the afternoon, we saw British troops moving on the shore of Lübeck Bay. At the same time, 12 British warplanes appeared in the air over the steamships, and they began bombing the ships.

“As a result of the British bombing and strafing the German ships, approximately 12,000 men died, a large number of which were Soviet prisoners of war.”

Witness Ye.N. STRANDBERG, questioned on September 14, testified:

“On May 3, 1945, in the middle of the day, the steamships Cap Arcona and Thielbek were sunk in the same bay by English aircraft.

“At that time, English planes flew over the steamship at low altitude several times and shot at people on the upper deck with machine guns. Then the planes disappeared. The Thielbek soon sank. Of the two thousand people on it, only about 50-60 people were saved, the rest drowned or were shot by the English planes, or else died from the explosions of bombs dropped from the same planes.”

Similar testimony was obtained from witnesses PANKIN, YEGOROV, and 14 others.

CHIEF OF THE 2nd MAIN DIRECTORATE OF THE USSR MGB

PITOVRANOV 24 September 1949