First, here are the “facts” as Russian historians know them, or believe them to be: Winter is coming in 1941, the first year of the tragic siege of Leningrad. German and Finnish forces are doing their best to completely encircle the city, and are finally able to do so when the Wehrmacht troops reached Lake Ladoga and captured Shlisselburg in early September. Germany next created a powerful stronghold, taking advantage of the geographical features between Shlisselburg and the village of Lipki. Within a month, the town of Tikhvin fell to the Wehrmacht, allowing German forces to cut off the road over which vital food supplies were transported for the people of Leningrad.

The encroaching colder weather brought freezing temperatures and opportunities – in November, it was impossible to break the blockade of the city from the Neva. However, it was possible to take advantage of the early wintry temperatures and launch a surprise attack from the north, from icy Lake Ladoga. The attack was to be carried out by the forces of the 80th Rifle Division and the 1st Special Ski Regiment of the Baltic Fleet sailors along the entire coast from Shlisselburg to the village of Lipki. But according to the Leningrad Front headquarters, the commander of the 80th Rifle Division, Colonel Ivan Mikhaylovich Frolov, and commissar Konstantin Dmitrievich Ivanov refused to carry out the attack in a selfish act of cowardice and treason.

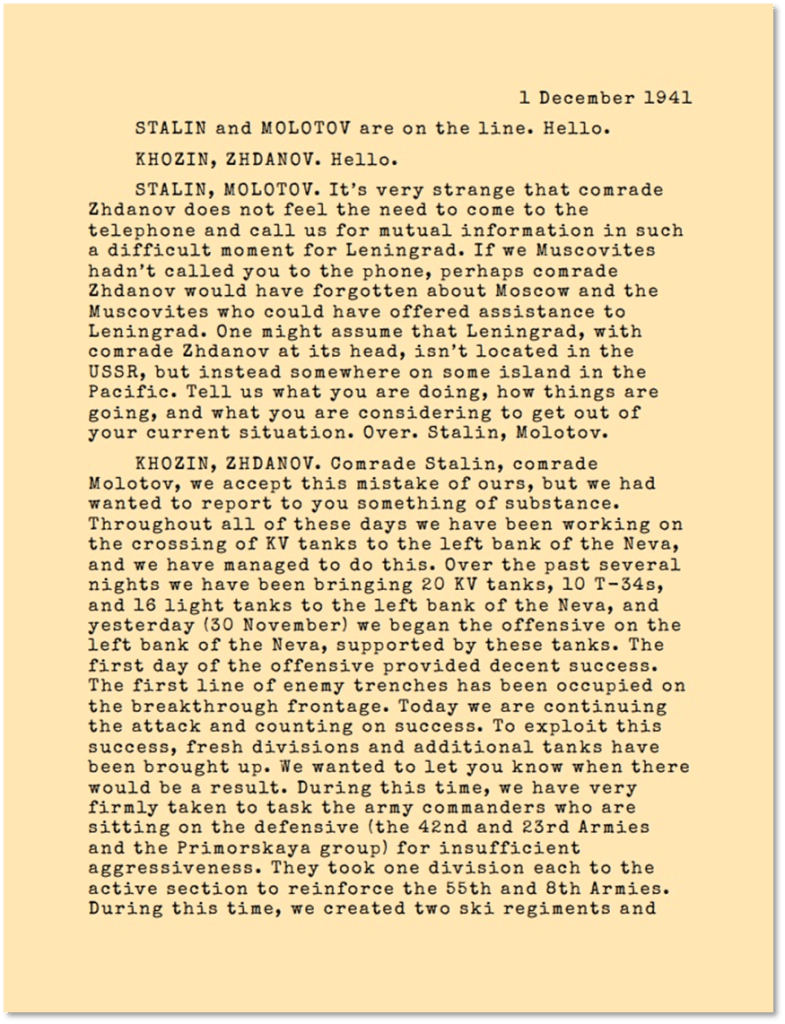

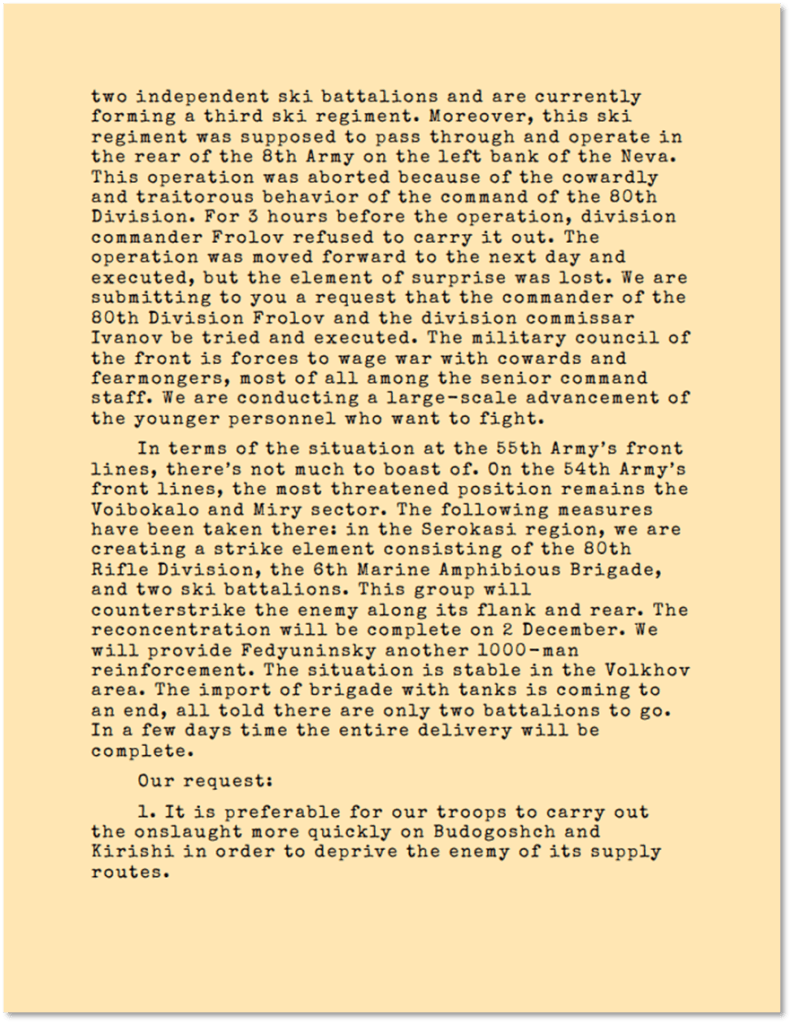

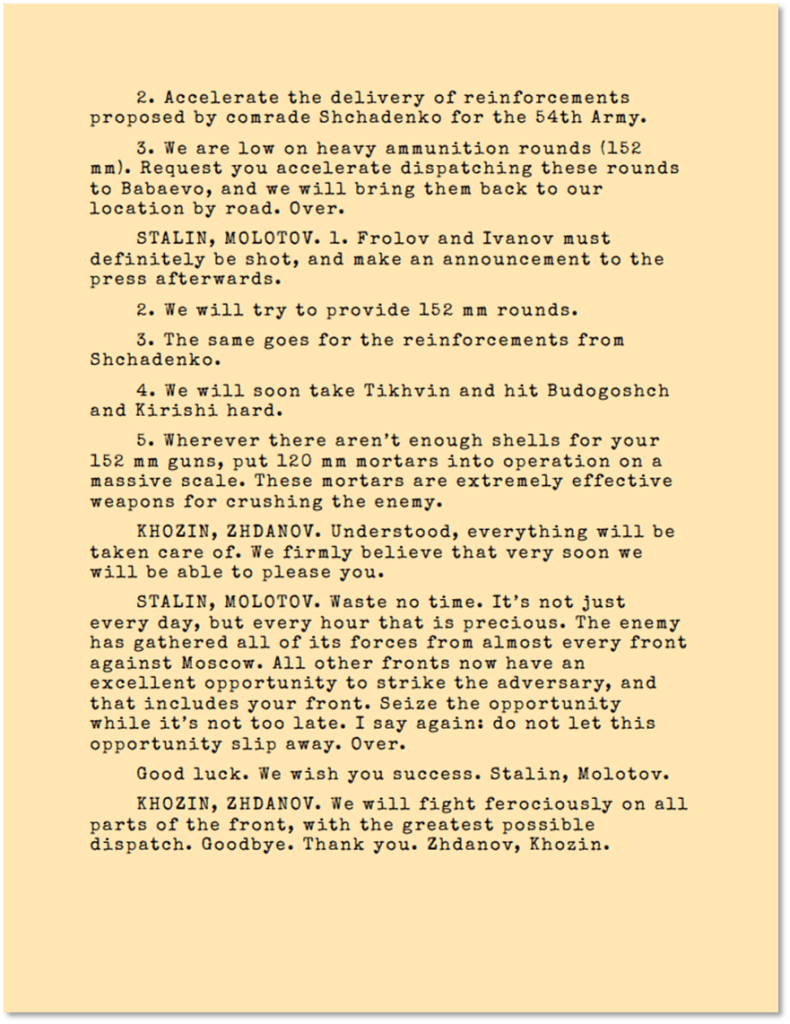

What follows are notes cobbled together from various declassified sources, including two sections of particular interest: first, the translation of a true transcript of a telegraph conversation between Moscow (Soviet leader Josef Stalin and Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov) and the Leningrad Front (CPSU Chairman Andrey Zhdanov and Commander Mikhail Khozin) in which Moscow orders Frolov and Ivanov to be executed and the media to be alerted; and second, extracts from Frolov’s verdict.

First, the rest of the story.

The 80th Rifle Division, led by I.M. Frolov, was formed in July 1941, made up of Leningrad residents, and was called the 1st Guards Leningrad Rifle Division of the People’s Militia. In August, the division fought heavy battles in the Kingisepp defense sector, and in September, near Leningrad. In late October, the battered division, pinned by the Germans to the Gulf of Finland, was transferred from the Oranienbaum bridgehead across the gulf by barges. But there was no time to rest or replenish the thinned ranks. A grueling multi-day march on foot to Lake Ladoga lay ahead.

The ski detachment was formed from 1,200 volunteer sailors immediately before the offensive. On November 21, it was headed by Major V. F. Margelov, the future Hero of the Soviet Union and the legendary founder of the Airborne Forces. In the fall of 1941, before his appointment as commander of the ski regiment, Major V. F. Margelov was one of I. M. Frolov’s subordinates. He commanded the 218th rifle regiment, which was part of the 80th division.

According to the verbal order received from the front headquarters on November 21, the division’s units were ordered to strike at the Wehrmacht positions in the area of the “bottleneck” from the side of Lake Ladoga, and then move in the direction of the Sinyavino highlands to join up with friendly units breaking through from the Nevsky Pyatachok.

Ivan Mikhailovich Frolov understood that this order, dubious in itself, given the low combat readiness of the division, could end in failure. Trying to prevent tragedy, he directly reported to the Chief of Staff of the Leningrad Front, Lieutenant General D.N. Gusev, that the division was weak, not ready for an offensive, and unable to carry out the order.

And that was the case. The operation began on the night of November 26, 1941. The first attack on the open ice floe petered out when the enemy opened fire. The next one was undertaken before dawn on November 28. The actions of the division units with Margelov’s ski detachment were not sufficiently coordinated and agreed upon. The infantrymen were supposed to break through first, and the skier-sailors were supposed to support this attack. They advanced from Ladoga to the city of Shlisselburg, focusing on the Bugrovsky lighthouse. The question of who was waiting for whom on the frosty night of November 27-28 is still not fully clear. Only one thing is clear – there was no joint action, the offensive ended in failure. Many infantrymen and sailors died under the enemy’s sudden heavy fire or drowned, as the fragile ice was broken by shells.

On the one hand, researchers of this topic note that the new command of the 80th Rifle Division brought units to the shore of Lake Ladoga with a five-hour delay. The commanders had difficulty orienting themselves in the situation, and did not know where the enemy positions were.

On the other hand, they write that soldiers from the 80th Rifle Division had to wait in the cold for the attack to begin.

In any case, there is a clear lack of planning for the offensive operation, haste and lack of coordination of actions.

On the night of November 28, the sailors launched an attack without the support of the 80th Division. They broke through the first line of enemy defense at the Novaya Ladoga Canal, occupied the village of Lipki, approached the Staroladoga Canal, but were unable to complete the assigned task (without infantry support). Of the 1,200 men, more than 800 marines were killed. Major Margelov was seriously wounded.

The following pages show a different story conveyed by Zhdanov and Khozin in a transcribed telegraph conversation with Stalin and Molotov on 1 December 1941. But before the report even begins, it is worth noting that Zhdanov received quite the lengthy reproach from Moscow on his inability to provide information on how things were going.

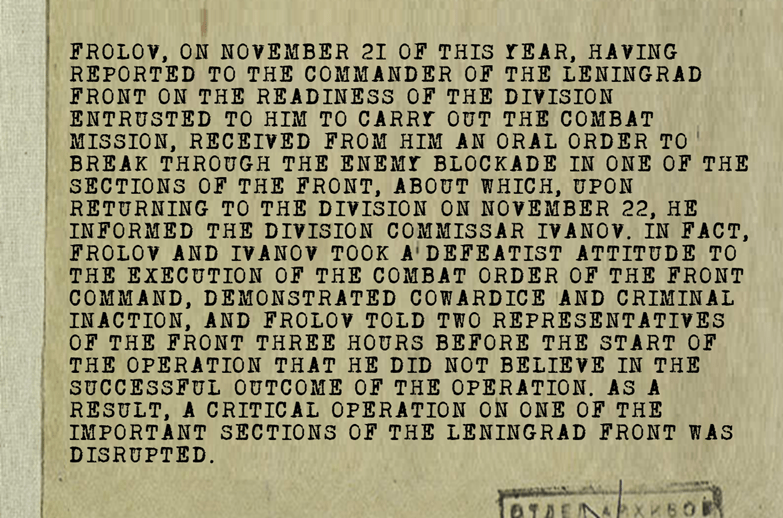

The order from Moscow was carried out as prescribed. On December 2, 1941, the military tribunal of the Leningrad Front sentenced the former commander of the 80th Rifle Division, Colonel I.M. Frolov, and the former commissar of the same division, K.D. Ivanov, to death. Excerpt from the verdict:

In the verdict written by I. F. Isayenkov, who presided over this trial, the judgments on key issues of the subject of proof look strange and dubious. It feels like important moments for establishing the truth have been deliberately omitted or veiled.

First, it is evident from the verdict that there was no written order from the front commander to break the blockade. The document, marked Top Secret, for some reason does not indicate the section of the front where, based on the verbal order, the division’s soldiers were to carry out the combat mission.

Second, five days passed from the time the verbal order was given (November 21) until the start of the offensive. During this time, the division’s political and moral integrity had significantly declined, as it had to undertake a grueling multi-day march. According to veterans’ recollections, the soldiers were completely exhausted, and many died on the move – from hunger, cold and exhaustion. The lack of forage led to the death of horses.

“The march was very difficult – many soldiers died of hunger and exhaustion on the move. There was a shortage of ammunition and fodder, and the division itself was such only in name – until November 12, it had only two rifle regiments. In five days, from November 19 to 24, the division changed four concentration areas, the people were completely exhausted, and the horses began to die off from the lack of fodder.”

Third, the notion about the postponement of the operation to another day due to the fault of the division commander raises serious doubts. But even if this was true, it essentially did not change anything, since today it is a matter of record that the German command knew from defectors about the upcoming attack and was fully prepared to repel it. In addition, after the unsuccessful attack on November 26, a new order for an offensive was given the next day.

Fourth, the operation to break the blockade, the failure of which led to an investigation and then a trial, was not led by Colonel Frolov, but by the new command of the 80th Division. It is known that from November 25 the division was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel P.F. Brygin, previously the commander of the 260th Regiment.

Why didn’t military lawyer Isayenkov pay attention to these obvious points?

It turns out he did. This was written about back in 1990 by V. I. Demidov and V. A. Kutuzov, citing archival documents and the story of I. F. Isayenkov himself: “In the autumn of 1941, a unit of the Leningrad Front operating in the direction of Mga failed to complete its combat mission. Whether the division commander and commissar were to blame for this, and if so, to what extent, is now impossible to determine with complete certainty. The result is known: the military council of the front brought them to trial by a military tribunal. Front prosecutor M. G. Grezov accused the defendants of treason and demanded the highest measure of punishment for them – execution.

“We, the judges,” Isayenkov continued, “carefully examined all the circumstances of the case and found that such a crime as treason could not be discerned in the actions of these people: there was negligence, which is a whole separate matter, but there was no reason to deprive them of their lives… Grezov responded by complaining about the ‘liberalism’ of the tribunal to the Military Council. Zhdanov himself called me and began with a dressing down. But I told him: ‘Andrei Alexandrovich, you yourself always instructed us: to judge only in strict accordance with the laws. According to the law, there is no “treason” in the actions of these people.’ – ‘Do you have the Criminal Code with you?’ – ‘Yes…’ I leafed through it, showed it to the other members of the Military Council: ‘You did the right thing – in strict accordance with the law. And in the future, act only this way. And with these two,’ he added a mysterious phrase, ‘we will deal with them ourselves…'”

The solution to this riddle lies in the Central Archives of the Ministry of Defense – a one-page document of the “troika” (the prosecutor, the head of the political department and the head of the special department of the NKVD of the front): the accused themselves admitted that they had in fact betrayed the Motherland – “we propose to shoot them extrajudicially…”

However, judging by everything, I.F. Isayenkov had to sort it out. As already mentioned, the author found only an uncertified copy in the archive of the Leningrad Military District military tribunal. But there is hardly any doubt that the tribunal’s trial formally took place, and the judges signed the verdict. After all, evidence about the trial has also been preserved, even the wounded major V.F. Margelov was brought to the court hearing on a stretcher (according to another version – on crutches) for questioning as a witness, and the convicts supposedly asked him for forgiveness for the death of the sailors.

In 1957, the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR overturned the verdict of the military tribunal of the Leningrad Front of December 2, 1941 against Ivan Mikhailovich Frolov and Konstantin Dmitrievich Ivanov and closed the case due to the absence of criminal elements in their actions.