Earlier this week, the official website for the Rosatom State Nuclear Energy Corporation published an article on newly revealed activities of the nuclear industry’s counterintelligence organs. We’re translated the article and are happy to provide it to our readers.

Nuclear Secrets of Department “K”: Counterintelligence Activities in the Development of Russia’s Nuclear Industry

1 December 2025

Eighty years ago, on November 15, 1945, Department “K” was created within the People’s Commissariat of State Security (NKGB) of the USSR. Its mission was to provide “operational security services to special-purpose facilities,” that is, enterprises and organizations of the fledgling nuclear industry.

“The Soviet Union’s development of its own nuclear weapons under the most brutal wartime and postwar conditions of the 1940s was a triumph for the entire state apparatus—scientists, designers, engineers, builders, administrators, and, of course, the intelligence services. While the contribution of foreign and military intelligence to the Soviet atomic program is well known thanks to recently-published memoirs and declassified documents, the role of counterintelligence in this global project remains less well-studied,” Oleg Matveyev, a historian of the intelligence services and an expert at the National Center for Historical Memory under the President of the Russian Federation, explains in an article for RIA Novosti. The text is reproduced here, slightly abridged.

“Problem No. 1”

The United States tested its first atomic bomb on July 16, 1945, and on August 6 and 9, 1945, it bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This marked the beginning of the Soviet-American nuclear arms race.

On August 20, 1945, the Soviet leadership decided to establish a Special Committee under Lavrentiy Beria and create a “headquarters” for the Soviet atomic industry—the First Main Directorate (PGU) under the Council of People’s Commissars, headed by Boris Vannikov, People’s Commissar for Munitions. In 1953, the directorate was transformed into the Ministry of Medium Machine Building.

Ensuring secrecy in the First Main Directorate was entrusted to the security service (2nd Department) based on the 5th Special Department (control over the production of gas masks), transferred from the NKVD of the USSR, and to officers who came from the Main Directorate of Counterintelligence (SMERSH).

The fact that the Soviet Union had begun developing an atomic bomb was no secret to the United States. This was clearly indicated by the removal of nuclear physicists, laboratory equipment, and uranium ore reserves from defeated Germany, as well as the launch of the Soviet-German Wismut plant in the Ore Mountains of Thuringia and Saxony. But the technology had to remain secret.

“The operational and command staff of the units that provided the counterintelligence support for work on ‘Problem No. 1’ (as the atomic bomb project was documented) were primarily tasked with ensuring the strictest secrecy of the work being carried out, preventing foreign intelligence agents from penetrating both the facilities and their immediate surroundings, and identifying the intentions of foreign intelligence agencies and the extent of their knowledge of the work underway in the USSR,” says Oleg Matveyev. “The state security agencies were also tasked with providing physical security for the leading scientists involved in the Soviet atomic project.”

Special commissioners — generals and senior officers of state security agencies — were appointed to oversee the laboratories, design bureaus, factories, and construction sites associated with “Problem No. 1.” Thus, the work of the scientific “headquarters,” Laboratory No. 2, headed by Igor Kurchatov, was overseen by Nikolai Pavlov, who became a general at 31 (then the youngest general in the USSR) and, at the end of the war, headed the NKVD Directorate for the Saratov Region. He would soon become First Deputy Head of the PGU, then Head of the Main Directorate of Experimental Designs at the Ministry of Medium Machine Building, and, in 1964, Director of KB-25, which developed nuclear weapons and their components (now the Dukhov All-Russian Scientific Research Institute of Automation).

From Kremlyov to Sarov

Secrecy was maintained not only in laboratories and production facilities. It also extended to life in closed cities. For example, to preserve the anonymity of the atomic project’s main design organization, the name of KB-11 (the nuclear center in Sarov) was repeatedly changed: “Object 550,” “Base 112,” “Privolzhskaya Office of Glavgorstroy,” and so on. In 1954, a classified decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR granted the settlement of KB-11 the status of “oblast city” [regionally governed city] with the name Kremlyov. In 1960, the atomic city became Arzamas-75. From 1966, it was Arzamas-16. In 1994, the city was declassified and again became Kremlyov, and in 1995, it received its current name.

All employees hired by KB-11 were thoroughly vetted. Their personal correspondence was sent to Moscow, Center-300. Letters were prohibited from disclosing any information that could reveal the location of the facility, such as the names of rivers, nature reserves, churches, and cathedrals.

Securely Hidden

Counterintelligence was doing its job: the US failed to accurately predict the date of the test of our RDS-1 nuclear device. It took place on August 29, 1949, at the Semipalatinsk test site. The Americans believed it would not happen before the first half of the 1950s.

Washington’s ignorance of the real state of affairs in the Soviet nuclear industry is also indicated by a message sent to Lavrentiy Beria in November 1949. Case in point: according to military intelligence, the Americans had no precise information about the locations of Soviet nuclear cities (one was believed to be located near Lake Baikal). The West also believed that only the third test at the Semipalatinsk test site was successful; the first two allegedly failed.

“The Soviet leadership recognized the excellent work of counterintelligence. Deputy Chief of the First Chief Directorate, Lieutenant General Pavel Meshik, and Head of Department ‘K’ Ivan Pisarev were awarded the country’s highest award — the Order of Lenin — for ‘successfully executing a special government assignment,’ in accordance with a top-secret decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated October 29, 1949,” says Oleg Matveyev.

While Soviet intelligence had its own people in the Manhattan Project (the US nuclear program), American intelligence had nobody in ours. “The Americans had no informants in the USSR’s atomic structures, the Special Committee, or the First Directorate,” Oleg Matveyev asserts.

Search for Spies

Large counterintelligence forces were deployed in the Urals. The first complex for producing weapons-grade plutonium (Plant No. 817, now Mayak) was built in the Chelyabinsk region, and the first industrial uranium enrichment facilities were built in the Sverdlovsk region.

A special message to Stalin from State Security Minister Semyon Ignatiyev, dated August 1951, has been declassified, in which Ignatiyev wrote that a certain Osmanov, an American intelligence agent who had defected to the United States while serving with the Soviet troops in Germany, had been detained in Moldova. Osmanov admitted that he had been dropped off by plane from Romania and was supposed to travel to the city of Kyshtym in the Southern Urals “to gather information about enterprises involved in nuclear energy production.”

As Vladimir Khapayev, a retired KGB Major General and veteran of nuclear counterintelligence, recalled, in 1953, the Americans infiltrated an illegal agent named Vladimirov into the USSR. He was tasked with obtaining information about a nuclear facility in the Urals. Vladimirov was detained in Ukraine. During interrogation, he detailed the mission and instructions on how it was to be carried out. Later, Kathy Korb [sic], an employee of the GDR representative office at the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance in Moscow, was exposed as an American intelligence agent who had been ordered to obtain information about the special facility.

Mysterious Uranium-5

In nuclear slang, uranium-235 was known as the fifth uranium at the dawn of the nuclear project — the primary radioactive isotope for nuclear weapons, produced through enrichment at specialized plants. The first such facility was Plant No. 813 near the village of Verkh-Neyvinsky in the Sverdlovsk region. It is now the Ural Electrochemical Plant (UEKhK), the world’s largest uranium enrichment complex in Novouralsk, formerly Sverdlovsk-44. The Verkhneyvinsky Group was created within Department “K” to guard the facility.

Plant No. 813 was of interest to foreign intelligence agencies for an obvious reason: it was there that industrial enrichment of uranium-235 in gas centrifuges began. In 1962, the first industrial phase of the world’s first centrifuge uranium enrichment plant — significantly less energy-intensive than gas diffusion — was launched. This was a colossal technological breakthrough. The technology remained a top state secret and was only revealed in the late 1980s, when a delegation of US specialists was allowed into the UEKhK [Ural Electrochemical Combine].

According to Oleg Matveyev, maintaining the strictest secrecy led the Americans to delay their development of gas centrifuges, thus never creating a fully-fledged gas centrifuge industry. Meanwhile, Russia, thanks in part to counterintelligence, firmly maintains its leading position in the global uranium enrichment market.

Cost-cutting can be harmful

Counterintelligence agents weren’t solely concerned with protecting state secrets. They uncovered conditions that could lead to emergencies involving special equipment and nuclear warheads. State Security Colonel Stepan Zhmulev, deputy director of the Sarov Nuclear Center for Security and Safety, and later deputy head of the Security and Safety Directorate at the Ministry of Medium Machine Building, recalled the following story: In the mid-1960s, when improving nuclear warheads, considerable attention began to be paid to saving production costs. Then, KGB officers halted the testing of a nuclear warhead. It had already passed expert assessment for full test readiness, but the KGB received advance information that the device was unfinished. After a thorough inspection, this information was confirmed. As Stepan Zhmulev wrote, the nuclear center’s scientific director, Academician Yuli Khariton, stated at a general meeting: “The Chekists were right; the device really was insufficiently developed.”

Work in Chernobyl

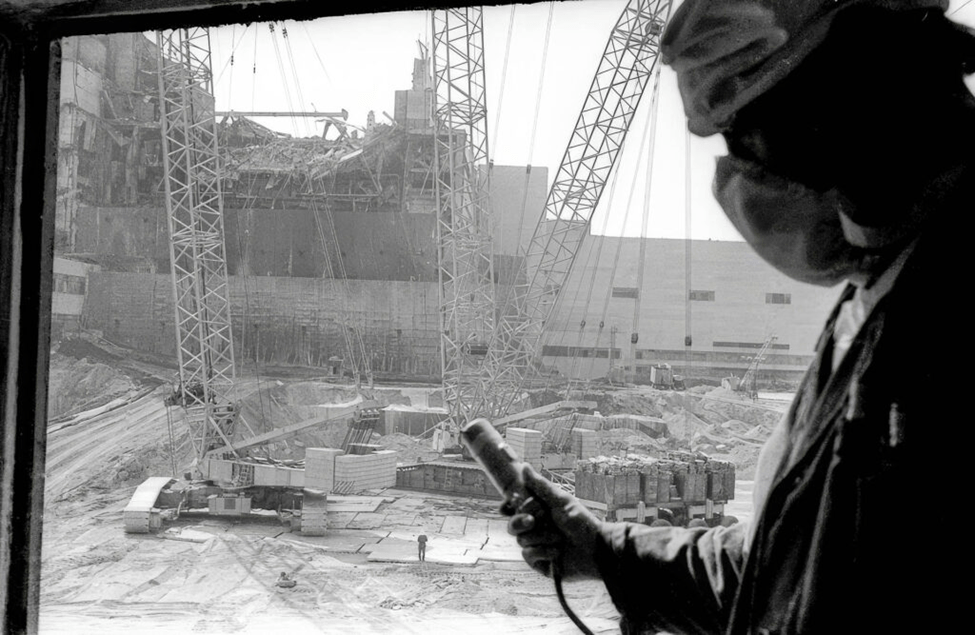

Among other things, state security officers were required to promptly identify vulnerabilities that could lead to accidents at nuclear facilities. Declassified documents indicate that counterintelligence officers reported deviations from standards during the construction and operation of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, but their voices went unheard: the builders were eager to report the completion of the work in time for the next national holiday.

KGB officers played a major role in the investigation of the causes and mitigation of the aftermath of the accident at Unit 4 of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. On the night of April 26, 1986, immediately after the accident, officers from the KGB department in Pripyat headed to the epicenter of the accident. Along with firefighters, plant workers, and medical personnel, the counterintelligence officers found themselves in the nuclear inferno. All received high doses of radiation and were hospitalized.

The KGB carried out extensive work to prevent agents and career foreign intelligence officers from entering Pripyat to determine the causes of the accident and learn how the Soviet state system operated in dealing with the aftermath. Many state security officers had to be replaced for medical reasons. KGB officers were dispatched from across the country. But, as those involved in the events recalled, drawing parallels with military operations, not a single counterintelligence officer refused to carry out the mission.

Counterintelligence in modern history

In the early 1990s, the territorial secrecy surrounding the nuclear cities lost its former significance, and restrictions on scientists and specialists traveling abroad were gradually lifted. However, foreign intelligence services did not diminish their interest in Russian nuclear technology.

A major victory for our counterintelligence in the mid-1990s was the thwarting of a German intelligence operation to smuggle plutonium allegedly of Russian origin. According to anonymous FSB veterans, the goal was to accuse Russia of failing to secure its nuclear arsenal and ultimately establish “international control.” Thanks to the professional work of state security officials led by Mikhail Dedyukhin, the Germans were forced to admit that the plutonium was not Russian. A national scandal erupted in Germany, and those involved in the operation were punished.

Translation © 2025 by Michael Estes and TranslatingHistory.org