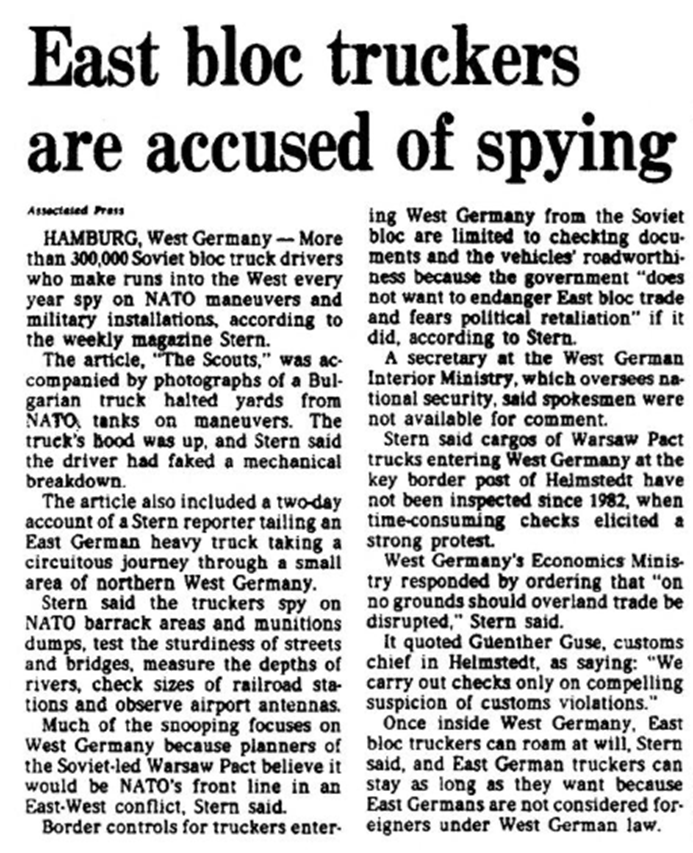

Every now and then, while researching other materials being translated, I’ll bump into a curious news article that catches the eye and won’t let it go. For example, this gem from the Philadelphia Inquirer from 10 January 1986:

As I was living and working in West Berlin at the time, many kilometers within the bowels of East Germany, I should have caught wind of this information and not have been surprised some 40 years later. But the date this article was published happened to coincide with the day my wife and I tied the knot and began our journey down the path of wedded bliss. Accordingly, I hope I might be afforded a small bit of leniency in this case.

I was able to track down the article referred to above in the 9 January 1986 copy of Stern. The six-page article provides a bit of a chilling look at priorities at the time, with cooler heads recognizing that stopping every truck coming through the country can’t be stopped, even with compelling evidence of ‘visual espionage’ being carried out, as the political and economic consequences could be quite jarring for all sides. Regardless, it’s a fascinating glimpse back into the days of the Reagan-Gorbachev Cold War, when things like troop movements and weapon capabilities/limitations were considered quite sensitive.

While Russian is my forte, I borrowed a few friends to help me out with the German in the following translation. If you detect some strange wording, I’m happy to take the blame and shuffle off to my Russian materials from this point on. But this was too interesting an exercise to pass up. Enjoy!

The Secret Trade of East Bloc Long-Haul Truck Drivers: How Spying Goes on in the FRG

R. Müller – Stern No. 3, 9 January 1986, pp. 14-20

EAST BLOC ESPIONAGE

“The Scouts”

More than 300,000 trucks from the Warsaw Pact countries drive the roads of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) every year. Their official job is to transport goods. But many East Bloc truckers have additional instructions: they gather information for their countries’ secret services. Worried about possible political consequences, Bonn abstains from countermeasures.

Trucks in all of the restricted areas

37% of the FRG is closed to members of Soviet military delegations. These institutions are remnants of the Occupation. For violations of security controls, the former Western Allies have exclusive policing power. The Soviets have often abused their observer status for espionage purposes, and therefore have had their freedom of movement heavily restricted by the British, French, and Americans. Trucks from the Soviet Union and other East bloc countries, however, can drive unhindered through the prohibited areas.

We have moved into position two hours before the arrival of the first tank. It is 4:00 AM, and we are at the ‘Donautal’ [Danube Valley] rest area on inter-Europe Route 5, the famous ‘Orient Line’. An immense reinforced concrete bridge here, near Passau, connects the foothills of the Bavarian Forest with the Neuburg Forest. Deep in the valley flows the grey-brown muck of the Danube, squeezed as if in a corset between the road on the northern bank, and federal highway 8 and the Passau-Vilshofen railroad line on the southern bank. In the dark and fog which hangs like a blanket over the river, the downs downstream from the bridge – Schalding, Wörth, and Heining – are barely visible.

At 6:00, one kilometer east of Schalding, the Bundeswehr will cross the Danube with heavy equipment while further west, near Regensburg, paratroopers are to commence action. We are not the only curious ones here this early morning, waiting for the “Hohn Welle” maneuver to begin.

17 barges from Hungary, Romania, and Czechoslovakia are anchored right and left of the drill area. They have left an alley clear in the middle – where the Bundeswehr plans to try its Danube crossing. Western ships are nowhere to be seen.

On land, the East Bloc presence is even more impressive. More than 100 tractor trailers have gathered at a cargo container terminal in the middle of the drill area. They are all trucks from East Europe. They too have left room in the center, where the military transports loaded with sleepy draftees will be directed precisely at 6:00 AM. Interested Bulgarian, Czech, and Romanian truck drivers mingle with the drilling troops.

Suddenly it gets loud. A cargo train rumbles over the land. It carries tons of military freight: LEOPARD tanks and 155mm howitzers on self-propelled gun mounts. Soldiers maneuver the costly war machinery from the cars down ramps, and place them one at a time in the remaining free space at the container terminal – surrounded by East Bloc trucks. Gun after gun, tank after tank, everything is transported across the Danube by waiting ferries.

The free place in the middle is absolutely full. Our gaze can barely take in the crowd from our position. The driver of a refrigerated truck with the white and blue inscription “Romania” on the sides has the same problem. The Romanian starts the heavy truck and drives a few hundred meters higher, to the “EC Slaughterhouse, Passau” in the locality of Heining. He doesn’t park on the loading ramp, but crossways in the road. From there he has an exceptional view of the Danube – and the Bundeswehr maneuver. We watch him for 6 hours on his ‘commander’s mound.’ Neither he nor his co-driver left the truck in that time to load or unload, but busily took notes. Only occasionally did he have to move back and forth, when trucks going to the slaughterhouse had trouble getting past the diagonally-parked vehicle. The Romanian left when the last tank reached the other bank.

Like him, a Bulgarian also seems to have been upset at the poor visibility. At the very beginning of the maneuver, he drive away from the group of parked trucks, stops 20 from the Bundeswehr loading ramp, gets out and raises the blue cab of his truck. In this way, the 45-year-old man in blue overalls and beige turtleneck sweater wants to indicate that his truck has broken down. He places a white plastic canister with BG (for Bulgaria) CE-2828 next to his vehicle. He looks briefly at the ending compartment, but decides he would rather take a walk and stroll toward the Bundeswehr soldiers.

The man walks back and forth from one end of the terminal to the other for 6 hours, meeting a colleague here, stopping for a chat there. He also seems to know the crew of a Hungarian truck parked here. When the last tank has reached the other shore, the Bulgarian goes to his truck, puts the cab back in place, and disappears on the autobahn in the direction of Regensburg.

Two other Romanian refrigerated trucks, which we watch at the ‘Danube Valley’ rest area for hours, also develop a particularly sharp interest in the maneuver area. They come on the Regensburg-Linz Autobahn, steer past the rest area onto a narrow drive with their 22-ton vehicles, turn under the autobahn overpass, and drive in the opposite direction back toward Regensburg, exit once again after 2 km at Passau-Nord, and come back to the ‘Danube Valley’ rest area. So it goes for hours and hours, always in a circle. As soon as the ‘Hohe Welle’ is finished in the early afternoon, the duo finally disappear over the Austrian border.

Whatever the unannounced maneuver-spotters from the East were able to see and hear on this exercise day – their visit was no surprise for the troops. For years, trucker-scouts from the Warsaw Pact countries have been present at all large Bundeswehr exercises, and East Bloc ships are always particularly numerous in our waterways if a maneuver is announced in the area. Some stand out by their oversized antennas, others by their peculiar freight. For example, Soviet truckers have transported peat thousands of kilometers from a moorland near Moscow to Freiburg, only to sell it cheaper than the local competition. And GDR trucks have driven from Magdeburg directly through the building rubble of West Germany, and taken 6 days for a 300-km stretch. It is not just a suspicion that these transactions have less to do with the transport of goods between East and West than with the gathering of information.

The work of these rolling spies is generally not adventurous espionage, such as the spy thrillers love to describe. It is, however, an important part of the current Eastern espionage effort – a supplement to what which the bribed ladies in Bonn anterooms, the enemy moles in the secret service, and the intelligence satellite above us are able to employ.

More than 300,000 Eastern trucks drive through the FRG every year. While some Warsaw Pact countries demand a comprehensive record from the drivers, and urge them to report everything that could be even remotely useful, others give the drivers special assignments.

They scout out barracks, look for munition depots, test the load-bearing capacity of bridges and roads, measure the depth of rivers and fords, note down the capacity of railroad stations and trains, report on new antennas at airports, are interested in the repair time for tanks and transporters in maneuvers, and in hit rates during firing practice.

For the yearly Autumn Maneuvers, it even becomes a cooperative effort, The East German, Polish, and Soviet trucks concentrate at that time in the North of the FRG; Czechs, Bulgarians, Hungarians, and Romanians in the South. From the abundance of small and even miniscule pieces of information, analysts in the Warsaw Pact capitals can put together a picture of the FRG that is always up to date.

West German authorities report parked GDR transporters in front of munitions bunkers, military airports, and missile sites on a daily basis. A Bundeswehr sergeant major reported that a Deutrans truck parks right next to the entrance of the German Research Institute for Air and Space Flight in Braunschweig at least twice a month for several hours. Another sergeant saw two Soviet transporters driving around on the Black Forest highway in the vicinity: they were original chassis from FROG 4 missile transporters. The Bundeswehr can only guess whether this is an attempt to test the maneuverability of enemy missile transporters on West German roads.

Since Eastern truckers seldom cross the threshold of ‘hard’ espionage, and mostly stick to so-called visual reconnaissance, it is hard to get a hold of them. According to the [FRG] constitution, drivers from the GDR enjoy full freedom of movement just like West German citizens. They may stop here as long and as often as they like.

Police ‘checks’ are limited to personal papers and condition of the vehicles – worn-out tires or dirty headlights. In practices, not even the contents are examined. ‘We only check for customs offenses when there is reasonable suspicion (i.e. probable cause),’ Günter Guse confirmed to us; he is Chief of the Main Customs Office in Braunschweig, which is responsible for the Helmstedt border crossing.

Soviet transporters are dealt with just as liberally. The USSR applies in Bonn for 10,000 visas per year for its truckers. They receive ‘Zählkarten’ [‘census papers’] with a visa for one year. Their vehicles display the TIR symbol. TIR means ‘Transport International Routier’ [International Transport of Goods by Road] – and trucks with this license plate must be cleared quickly and simply, according to an international customs agreement. Especially if they are sealed. Customs can only open them when there is ‘reasonable suspicion’.

Once Soviet trucks – and those of the other East Bloc countries – are in the FRG, they basically have no more checks to worry about. Their stopover times and routes are not prescribed, as they are for the members of Soviet military liaison missions on West German land. These institutions are relics from the Occupation after World War II. The British, French, and Americans have declared 37% of FRG land as restricted areas for the Soviets. Violations of the order cannot be punished by Germans, only by the former Allies.

While the range of the Soviet military liaison missions – suspected to be espionage centers – is decidedly restricted, Soviet trucks can drive unhindered through the restricted areas. That is what makes them so attractive to the Kremlin’s secret services.

Western news agencies have learned from East German and Soviet defectors that members of a special unit of the Soviet Army – called ‘Spetsnaz’ – are occasionally at the wheel of Russian trucks. These ‘special-purpose’ troops – comparable to some Ranger units in the US Army – would probably operate behind enemy lines in the event of war, and clear the most important obstacles out of the way of advancing units by conducting sabotage and assassinations. The Spetsnaz units, alleged to have 27-30,000 men, are made up of young career soldiers. Disguised as truck drivers, the Spetsnaz agents assigned to the FRG have already been able to inspect their designated areas, in order to be extremely well prepared, in the event of an emergency, to carry out their sabotage.

According to information from defectors, the GDR also has such units at its disposal, who are trained at the 40th Paratrooper Battalion in Lehnin near Potsdam. Some are assigned within the workers’ militia to special troops of six men each. The larger state-owned firms in the GDR, according to agents’ reports, are ‘pate’ [‘godfather’] to corresponding businesses in the FRG. The militias of the Mathias-Thesen Shipyard in Wismar, for example, are responsible for the Howaldtswerke-Deutsche Werft AG in Kiel. Specialists in the Wismar company militia, who would prepare to take over the Kiel shipyard in the event of a conflict. have already been able to look over their objective under the guise of Deutrans drivers.

It’s not just the FRG that the trucker-spies have their eyes on. The Deutrans, Sovtrans, Hungarocamion, or Romania trucks operate all over Europe, constantly number in the tens of thousands, are omnipresent, and behave peculiarly everywhere:

- In late April 1984, a Sovtrans tractor thundered over tank tracks in Skövde, Sweden, which are not marked on any map, right into the middle of a Swedish maneuver; other Soviet trucks followed the neutral company’s troops even down the smallest side roads;

- Starting from Finland, a Soviet truck needed 2 weeks to make the 3-day trip (through Sweden) from Haparanda to Trelleborg. Its several-hundred-km detour regularly led him past military installations;

- Switzerland turned away a Soviet truck in July 1984 which had 207 packages weighing 9 tons, all declared as ‘diplomatic luggage’ to be delivered to Geneva. The truck then drove back through the FRG into East Germany. West German customs officials who, like their Swiss colleagues, suspected electronic spy equipment, had to be content with a glance at the closed cartons because of political considerations;

- In Holland, a Sovtrans was stopped on a dike between the Den Helder naval port and the Leeuwarden NATO air base. It had supposedly only gotten lost – and went for a drive 150 km north of the route it should actually have been on;

- The French are plagued time and again by Bulgarian truckers, who often stop for days in front of the Paris secret service headquarters on Blvd. Mortier, the navy yard in Toulon, or the nuclear submarine port in Brest.

- Since 1983, Norway has increasingly observed ‘long trip times’ and ‘deviations from normal routes’ by Soviet transporters.

- Finally, the Austrians are complaining about unusual activities of ‘coal ships’ on the Danube, such as the ULAN BATOR. Seven Soviet and Bulgarian barges with large-scale antenna systems observed the Autumn Maneuver of the alpine country’s federal army: supposedly the ships had engine trouble and could not move themselves from the exercise area. The ‘repair time’ was used to identify the frequencies of the maneuvering troops. In the process they interfered with radio communications, and started a regular ‘war in the ether’ with the Austrian signal battalion.

But nowhere in Europe are the spies more active than in the FRG – this country through which Soviet strategy plans its advance to the Atlantic in the event of a conflict. This strategy – the result of an historically-based fear of invading armies from the West – is meant, by a swift thrust, to prevent war from being fought on Russian soil, as it already has been twice in the century.

The new NATO Air/Land Battle Doctrine of 1982 is likewise a strategy of forward defense, which means, in a conventional war, clearing a hold on enemy land, in order to conduct the fighting there and to crush enemy reserves while still in their deployment area.

For both strategies, a detailed knowledge of the presumed first-hour battle arena, the area on either side of the East-West German border, is of utmost importance. The West works with superior electronics, satellite reconnaissance, and communications monitoring. The East does the same, although with more modest equipment, and makes additional use of the more economical methods of ‘visual reconnaissance’.

How exceptionally precise Soviet knowledge of the West German countryside is was demonstrated on 19 September 1984. On that day, NATO electronic specialists intercepted radio signals of the 3rd Soviet Shock Army. This elite Russian unit was on a maneuver in the Letzlinger Heide range near Magdeburg. Their 14th Tank Division was practicing ‘operations in the FRG.’ They simulated crossing the birder into the FRG from 6 km east of the border down of Hornburg. Another unit began the ‘attack’ 15 km southeast of Braunschweig. ‘The units and troops completed the next assignment, and took up position in the Hannover-Seesen sector,’ the intercepted situation report said on 21 September 1984 at 2400 hours. Later that same day, the 1st Division of the Tank Brigade supposedly stood 10 km south of Hannover, the 2nd east of Hildesheim, and the 3rd south of Peine. From their imaginary advance to the West, the Soviets seemed, to the amazement of NATO bugging experts, to know ‘every stone, every shrub, every bump in the ground.’

That this is the fruit of the labors of thousands of trucker-spies is considered established fact by West German news agencies. While liberal politicians admonish us to be calm, and are ready to accept the collection of detailed information by visual reconnaissance as the price of Western freedom of movement, right-wing representatives are demanding results. Willy Wimmer, Chairman of the Defense policy Committee of the CDU/CSU: ‘If our country is really like Swiss cheese when it comes to security, and it is only held together by the holes, then that damages our cooperation with our friends.’ Wimmer demands that ‘[West] German reconnaissance efforts be considerably stepped up and concentrated, without regard to departmental egoism.’ Money invested will protect us ‘sooner than many millions spent on procuring tanks, ships, and aircraft.’

The call for better protection against spies from the East is received with mixed emotions by the heads of West German intelligence agencies.

First, there is the difficult question of proof: visual reconnaissance is hard to get a firm handle on from a legal point of view, along with the fact that whatever the truck drivers do beyond that, they do without leaving much evidence. Two hundred surveillance experts from the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, military counterintelligence, and the Federal Office of Criminal Investigation [the Amt für Verfassungsschutz, Militärischer Abschirmdienst (MAD), and the Bundeskriminalamt (BKA)] tried to prove even one of the Deutrans or Sovtrans truckers guilty of espionage who were gathered once again en masse at the ‘Springendes Ross’ NATO maneuver – but in vain.

Next, a constant and systematic supervision of the routes of Eastern trucks would exceed the capacity of the secret services, and a delay of even a few minutes per truck because of stricter checks would lead to chaos at the border crossings.

But more than these technical difficulties, the authorities fear the political consequences of harsher treatment of the ‘rolling Soviet cadres’ (spy jargon). Bonn does not want to jeopardize trade with the East, and fears political reprisals concerning access to Berlin, for instance. Just as when Customs Chief Günther Guse allowed a GDR truck to be opened three years ago ‘because of reasonable suspicion of a customs offense’; a protest from the GDR Mission in Bonn was submitted within half an hour, warning against hindering East-West merchandise traffic. A telex was also received giving the Bonn Economic Ministry discreet advice not to interfere with trade under any circumstances. Since that incident no more trucks have been opened. There were simply no more ‘reasonable suspicions’.

Pressure from the GDR was also very direct in another instance in protecting the mobility of its driver corps. When two GDR drivers stood before a judge in Celle in March 1984, accused of taking photos of the ‘Bellende Meute’ maneuvers in the Weserbergland [Weser Uplands] from the cab of their Skoda semi on one of their most recent trips to the West, Deutrans lawyer Kral Pfannenschwarz gave formal notice that in the event of a conviction, far-reaching political consequences would follow. The GDR would then have to announce fundamental doubts about the security of all its drivers in West Germany. Impacts on international trade would not be out of the question. But it did not come to ‘far-reaching political consequences’ – the defendants were acquitted.

The GDR took appropriate steps nevertheless – but not by force, to be sure: after the Celle incident, a defector reported, they instructed their drivers not to take any cameras or other technical equipment in the trucks with them for the time being. One can get just as far with a trained eye.

Route of the Deutrans KE-2867 truck from Helmstedt into Siegerland

Itinerary of a Ramble: Stern followed a GDR truck for 48 hours on its shifty tour through West Germany.

Tuesday, 5 November 1985

8:02 AM. We wait at the Helmstedt border crossing for any random GDR truck, in order to record its route in the FRG.

10:47 AM. The first GDR truck, a Volvo cab with a trailer, rolls up to the customs barrier. Can (license no. KE-2867) as well as trailer (license no. KO-2335) display in dark blue, on both sides of the orange body, the words: ‘Dautrans International Transport of the GDR’ [Deutrans International Spedition der DDR]. On the doors of the cab it says ‘VEB Motor Traffic Eisleben’. The driver gets out briefly by the customs booth: a thin, brown-haired man, about 30-35 years old, about 1.75 m tall, wearing blue jeans, a dark-blue jean jacket, white tennis shoes, and a dark cap. He turns some papers over to the customs official, gets immediately back in the truck, drives directly onto the A2 Autobahn toward Hannover. We follow him. His speed runs between 90-100 km/h, depending on the slope of the road.

11:38 AM. The Deutrans truck leaves the autobahn at the Peine exit, takes three lefts to a shopping center, and parks. Here, the driver makes some notes before getting out and disappearing in a building supply store. He comes back to his truck with two plastic bags.

12:06 PM. Back on the A2 to Hannover. Past Herford and Gütersloh. Back in the direction of Dortmund.

2:35 PM. Beckum exit. The Deutrans truck turns right on Bundesstrasse 475 toward Neubeckum, but turns left again in Neubeckum – without stopping – and takes the road back to Beckum. He is basically driving in a circle now. Through Beckum without a stop, then the B475 to Söst.

3:11 PM. Downtown Söst. Suddenly the Deutrans truck stops on a very narrow road; the driver switches on the flashers, gets out, walks around his vehicle, watches the traffic, and speaks to passersby.

3:14 PM. Now driving on the B1 to Werl.

3:16 PM. After driving only 300 m, stops again in the middle of the heavily traveled road. The driver turns on the flashers again, but stays in the cab where he is studying a map and watching traffic in the rear-view mirror.

3:23 PM. After the flashers have been turned off, the Deutrans truck drives 100 m further via a couple of side streets onto Schwemekker St. The residential road is off-limits for trucks over 3 tons.

3:27 PM. The driver walks up and down the street once, then disappears, papers on hand, past a closed gas station into the buildings behind it, which are located next to the Federal Property [Bundesvermögensamt] and Customs [Zoll] buildings.

3:39 PM. The driver returns without papers. Back on the B475 towards Beckum; that is, the same road he arrived on.

3:44 PM. Turns right off the B475 to the B1. Past a curve, the Deutrans stops directly in front of a fenced-in villa and turns on the flashers. The villa, according to its inscription, belongs to the Bundeswehr ‘STAB FLARAK Regiment 13,’ that is, the 13th AA-Missile Regiment Staff. The gate is closed. No guards to be seen. In front of the villa is a black and white copy of a NIKE-HERCULES missile; in the garden to the left of the entrance, a large sign: ‘Military Security Area. Unauthorized Entry Prohibited. Caution – Firearms.’

The driver gets out, speaks briefly with a soldier first, then with some passersby, and freely inspects the villa entrance. Turns off flashers and drives on.

3:53 PM. On the B1 in the industrial area southeast of Söst, 300 m straight ahead, turn, 80 m back, left on Cöster St. to the firm of Hagen Batterie AG, which flies three flags over the gatehouse: a company flag, the West German flag, and a Red Chinese flag.

4:05 PM. The Deutrans driver pulls into the courtyard, which is not visible from outside, after a few words with the doorkeeper.

4:44 PM. Now driving on the B1, then the B229 to the Söst exit onto the A44 toward Dortmund.

4:51 PM. After going 9 km on the A44, the Deutrans truck stops at the ‘Söster Börde’ parking area, next to six Belgian military trucks. Two minutes later a police patrol car pulls up behind the GDR truck, which immediately takes off again.

5:11 PM. It is getting dark. A few km beyond the Werl intersection, a second GDR truck signals ‘our’ Deutrans to stop at the Am Haarstrang rest stop by blinking his lights. The two park in a remote place, where they can talk undisturbed.

5:16 PM. The second GDR truck leaves.

5:26 PM. ‘Our’ trucker turns on his headlights and cab light, studies maps and papers.

6:46 PM. Another GDR truck (license no. UM-03 04) parks next to ‘ours,’ turns all its lights out, while those of the Deutrans remain fully lit.

6:56 PM. A GDR semi (license no. TU-083) pulls alongside. Driver turns out the lights.

6:57 PM. A Deutrans tanker (license no. KC-8189) does the same.

7:00 PM. A semi belonging to the GDR firm Germina from Karl-Marx-Stadt (license no. TU-8029) takes the last free parking space.

It is very noticeable that all of the vehicles, excluding ‘ours,’ suddenly turn off their lights, but neither drivers nor co-drivers get out. Now there are a total of 14 GDR trucks in the lot.

9:17 PM. Three British military vehicles park next to the exit. The soldiers go into the rest stop to eat. A GDR truck frim Ilmenau/Thüringen pulls up behind the British trucks.

9:56 PM. The Deutrans driver, who has been studying maps and papers, taking notes, turns off his truck’s lights.

9:58 PM. The British vehicles leave in the direction of Dortmund. The truck from Ilmenau follows them.

Wednesday, 6 November 1985

5:43 AM. The Deutrans driver takes a quick wash in the meager rest-stop bathroom.

6:13 AM. Leaves toward Dortmund on the A44. The Deutrans truck is driving very peculiarly now: downhill at 30-40 km/h, uphill at 80-90 km/h, extraordinarily slow on curves – clearly these are tricks to identify pursuers. We have trouble remaining unnoticed. Past the Dortmund-Unna interchange.

7:02 AM. Turns left onto the A1. Via Holzwickede to Wuppertal.

7:46 AM. Exit at Düsseldorf-Holthausen to the Düsseldorf industrial area.

7:53 AM. Driver uncouples the trailer at the SVG yard.

[Translator note: Strassenverkehrsgenossenschaft – Traffic Cooperative, a union German transport companies.]

8:05 AM. Drives back on the autobahn with just the tractor toward downtown Düsseldorf.

8:37 AM. Drives onto the Oberbilk Federal Railway Grounds. Driver stays in the cab without doing anything perceptible. After 7 minutes, moves on.

8:59 AM. Federal Railway freight station in Flingern. Driver speaks with rail workers. Neither loads nor unloads. Surveys the grounds for a quarter of an hour. Back downtown.

10:52 AM. Trailer is reattached at the SVG yard. Driver makes notes.

11:08 AM. Drives on the A59 toward Leverkusen as far as Hilden.

11:28 AM. Turns off onto the A3 toward Frankfurt.

11:55 AM. Right turn off the Siegburg exit. Zigzagging through Siegburg. Now toward Köln-Troisdorf, then toward Bonn. Stops in Siegburg residential district. Driver questions passersby. Waits.

12:25 PM. Drives on to Federal Railway parcel goods loading zone at Central Siegburg RR station. Driver parks in front of the ramp, goes south on foot. Comes back at 1:12 PM. Nothing is loaded. Drives right through Siegburg, then turns off toward Frankfurt/Hennef-Sieg.

1:21 PM. Goes through a red light in downtown Hennef.

2:04 PM. Leaves the B8 before Altenkirchen, and turns left toward Herborn. As becomes clear later, the Deutrans driver wants to go to Hachenburg, 14 km away. But instead of following the road signs, he makes an 80-km detour through Roth, Wissen, and the Betzdorf-Bruche industrial area.

3:00 PM. The Deutrans drives along Karl Stangler Road in a Betzdorf residential area, prohibited to trucks over 3.5 tons. The driver keeps stopping, without getting out, crosses back and forth, takes the same street several times (including a one-way street in the wrong direction).

3:12 PM. Back on the B62. Through downtown Betzdorf toward Siegen. Right turn at Struthof.

3:19 PM. Drives past the towns near Elkenroth. Here we are only 4 km from a Bundeswehr restricted area. Instead of going in the direction pointed out to him with ample gestures from passersby, he drives ever closer to the restricted area. The road here is so narrow in places that oncoming cars must stop in order to let him through.

3:38 PM. Via Kirburg, finally back to Hachenburg. The driver has completed a circle. Uncouples the trailer at an empty gas station, drives 80 m further on Sayn St. to Heyden Leather Goods and unloads a couple of grey cardboard boxes. Then he drives back to the trailer, reattaches it, and goes to eat sausages.

5:12 PM. Back to the truck. Driver makes extensive notes on forms, compares maps, writes, reads. Drinks four cans of beer before going to bed at 9:25,

Thursday, 7 November 1985

5:18 AM. Light goes on in the Deutrans truck. Breakfast at 6:00. Hachenburg exit, over the B8 through Hennef/Sieg, continuing on the B8, then via the A3 to Köln and via Hilden on the A46 in the direction of Düsseldorf.

8:11 AM. The Deutrans again drives down from the autobahn, like yesterday, at Düsseldorf-Holthausen to the Düsseldorf industrial area, but this time parks across from the SVG yard on the property of the Henkel firm – that is, directly across from the place where he had already been yesterday at 7:53 AM and 10:52 AM. Since it can be proven that he has not loaded anything since then, but has only unloaded (in Hachenburg), the question remains: Why didn’t the Deutrans go to the nearby Henkel on Wednesday? Because apparently he is to load here.

8:35 AM. The Deutrans drives onto the scales at Henkel, then crosses the company’s property.

10:57 AM. The Deutrans leaves the Henkel property once again, gets on the autobahn towards Wuppertal.

11:38 AM. Traffic jams on the autobahn make pursuit difficult. Last sighted at the Wuppertal-Sonnborn interchange. We then lose sight of the nimble ‘VEB Motor Traffic, Eisleben’ driver.